STYMIED!

Understanding the misunderstood

and long-abandoned nemesis of match play.

“S” is the swing that we practice in dreams.

A stymie looks simple. ‘Tis not what it seems.

Carrie Foot Weeks, New Golf Alphabet (1900)

By John Fischer III

The stymie. Mention it today, and most golfers will not have a grasp of what it was, although the stymie was an integral part of the

game, or at least match play, until it was abolished in 1952 by the USGA and the R&A.

The exact source of the word stymie, or styme, or stymy is not clear. In golf it generally is used to describe having your ball blocked by that of another.

A possible source is Gaelic, “stitch mi,” meaning “inside me.” Anathema to the Scots is the theory that stymie came from the Dutch “strait mij” pronounced similarly to stymie, meaning “it stops me.” As early as 1300 “styme” was used to mean not see at all, as “not to see a styme.”

In 1785, the great Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote the following lines:

“I’ve seen me daze’t upon a time

I scarce could wink or see a styme.”

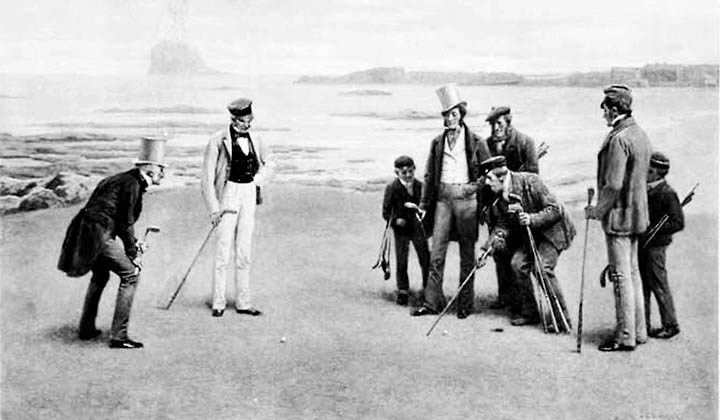

Regardless of the origin of the word stymie, it goes back to the very beginnings of the game when there were only two times a player was allowed to touch a ball, when it was teed up and when it was taken from the hole. Otherwise the ball was played as it was found.

This article is not meant to be a complete history of the stymie, especially since various golfing societies, clubs and associations had differing rules on balls blocking each other. In the beginning, the stymie applied to medal and match play.

“I think it merits a respected place in the game.”

Robert T. Jones Jr.

In 1744, the first rules of golf allowed that a ball could only be moved if it was touching another ball and in 1775, the Gentlemen Golfers of Leith allowed a ball to be moved if the balls were touching or within six inches of each other.

In 1812, the St. Andrews Golfers adopted the following: “When the balls lie within six inches of one another, the ball nearest the hole must be lifted till the other is played, but on the putting green it shall not be lifted, although within six inches, unless it lie directly between the other and the hole.”

The Montrose rules specified in 1830 that the stymie didn’t apply to medal play or four-balls.

In 1833, the St. Andrews Golfers abolished the stymie altogether but the following year reinstated it. In 1891, the St. Andrews Golfers (now the R&A) made reference to requiring a player to lift his ball that might interfere with another player’s stroke. This move appeared to remove the stymie from medal play.

In 1920, the USGA entered the fray with a one-year trial of allowing a stymied player to concede his opponent’s next putt thereby removing the stymie.

In 1921, the Western Golf Association abolished the stymie for its competitions, returned it in 1922 and then dropped the stymie for good in 1936.

In 1938 the USGA entered into a trial period of two years to allow a ball within six inches of the hole to be lifted without regard to the distance between the balls. This rule was made permanent by the USGA in 1941. In 1944 the PGA of America abolished the stymie in its competitions. Then, in 1950 the USGA abolished the stymie altogether, although the R&A retained it.

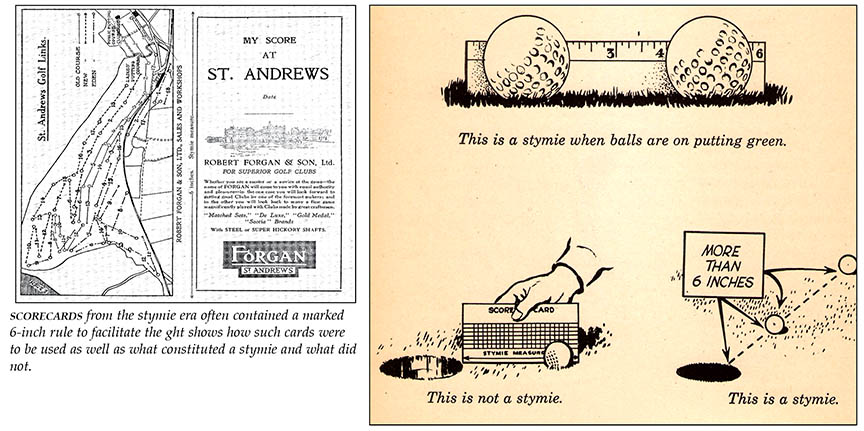

During the period stymies were played, many putters had a six inch measure on the shaft and scorecards routinely had a stymie measure. It was not uncommon for the card itself to have a side that was exactly six inches long.

Upon the adoption of the joint Rules of Golf in 1952 by the USGA and the R&A either the player or opponent could lift a ball on the putting green if it might interfere with a putt or assist the player, there being no penalty for striking another player’s ball on the putting green in match play.

In 1956 the rule was changed again so only the player could request an opponent’s ball to be moved. In 1984, the rule was again altered so that a ball could be lifted if it would interfere or assist another player, which is where we are today.

While wading through this summary of the stymie, its development and eventual deletion from the rules, one might ask whether the lifted ball could be cleaned. The simple answer is, “no.” While in play, until recently, the ball could not be cleaned other than to the extent of identifying it. That story is not covered here.

“The ball is the game. Remove it and nothing remains but to beat the air

or thump the ground with a stick.”

J.H. Taylor

Golf arrived in the United States from Great Britain, and the first rules were published in the United States in 1896 by MacMillan & Co., “The Rules of Golf, Being the St. Andrews Rules for the game, codified and annotated by J. Norman Lockyer, C.B., F.R.S., and W. Rutherford, Barrister-at-Law, Honorary Secretary, St. George’s Golf Club.”

The authors noted that they tried to explain the Rules as they applied to medal play, “owing to the absence in many cases of express legislation.” They also noted the by-laws of the Royal Wimbledon and of the Royal Isle of Wight Clubs were ignored because they each play under a Code of their own instead of the St. Andrews Rules.

While the Rules were imported and followed, American golfers as a whole never liked the stymie. It was viewed as a matter of luck or chance that interfered with fairness. Why should another shot, not under your influence, affect your play?

However, Bob Jones was adamant that the stymie had value stating, “with the stymie in the game match-play becomes an exciting duel in which the player must always be on guard against a sudden, often demoralizing thrust. More than anything else, it points up the value of always being the closer to the hole on the shot to the green and after the first putt. The player who can maintain the upper hand in the play up to the hole rarely suffers from a stymie.

“In my observation, the stymie has more often been the means of enforcing a decision in favor of the deserving player, rather than the contrary. I think it merits a respected place in the game. I know a return to it would greatly enhance the interest and excitement of match-play golf for player and spectator alike.”

The British, for the most part, accepted the stymie; it had always been a part of the game, something like “rub of the green.” Hard cheese, old boy, just part of the sporting nature of golf. In 1887, two-time winner of the British Amateur Championship and prolific golf writer Horace Hutchinson put it simply, “I tell you sir…that the man who would abolish the stimy (sic) would willingly break any law, either human or divine.”

Fearful that the USGA would succeed in abolishing the stymie, noted golf course architect Sir Guy Campbell wrote in a 1938 article for Country Life, “but to many golfers the stimy (sic) remains in match play as much a part of the many inspiring uncertainties of the game as a bad lie or rub-on-the-green, and for them its disappearance would be perhaps the last step towards the final mechanization of golf that would end its existence as a sporting pastime. Gods of chance and good intent forfend.”

Of course many stymies were the result of poor play or judgment; in fact, there were those who felt that a player who intentionally laid his opponent a stymie was a bit of a blighter, exceeding the unwritten bounds of fair play.

J.H. Taylor, one of the greats who dominated British golf winning The Open Championship five times from 1894 to 1913 commented, “I challenge anyone possessed of a decent mind to dare suggest that the player of any stymie since the game commenced has been activated by dishonest intentions. It would be an insult to his intelligence. Something that occurs accidently, without any suspicion of malicious interest, cannot by the stretch of the most elastic conscious be deemed dishonest.

“The ball is the game. Remove it and nothing remains but to beat the air or thump the ground with a stick.”

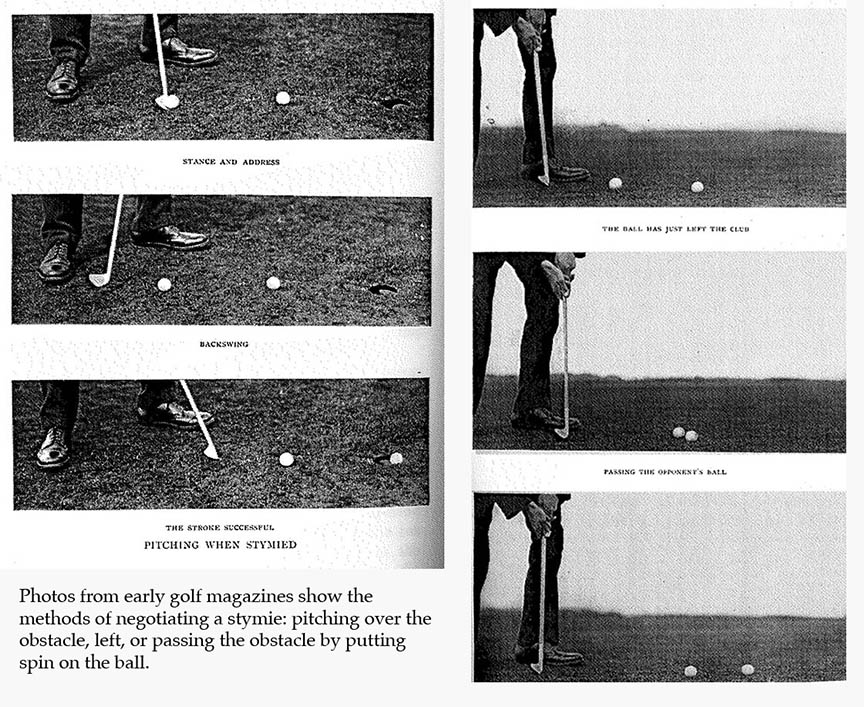

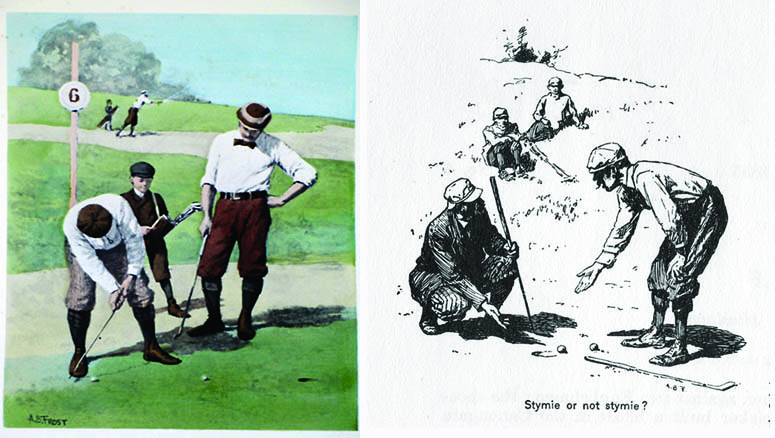

But the stymie being part of the game had to be dealt with by the player who was stymied by his opponent. If the ball was in a direct line between the hole and the player’s ball and could not be negotiated because of position, it was referred to as a “dead stymie.” A ball that only partially blocked the line was called a “partial stymie,” and in both instances there were ways of playing them.

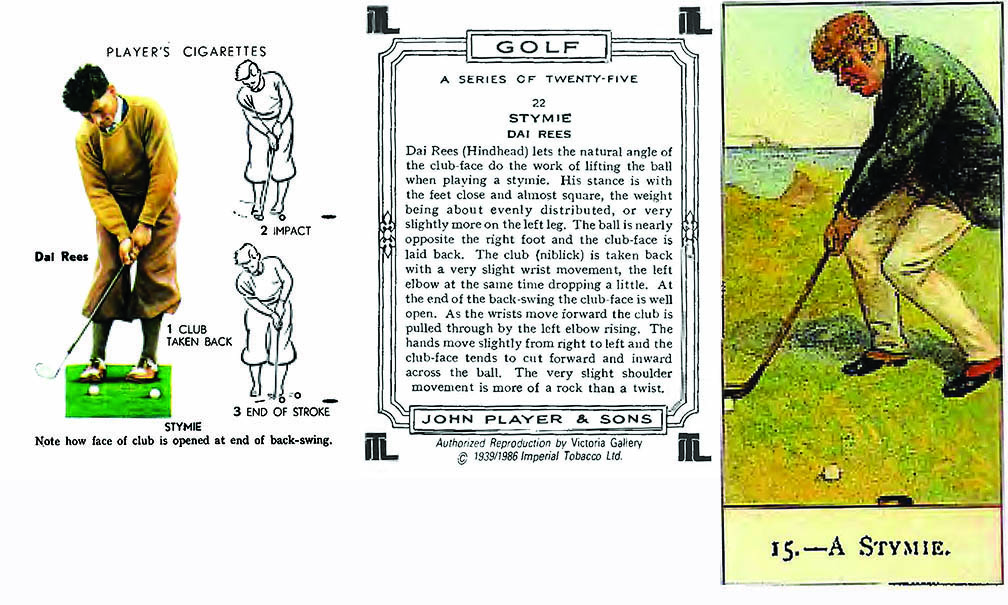

It should be noted that negotiating a stymie was probably slightly easier with the “smaller” British ball, at that time 1.62 inches in diameter. The “larger” American ball was 1.68 inches in diameter.

Harry Vardon had advice for playing the stymie. For a dead stymie, use a lofted club – mashie niblick or niblick – and pitch over the offending ball. For a partial stymie or a stymie where there was enough length to the hole, hit a cut aiming to the left of the cup and planning for the ball to die into the left side of the cup or to stop dead to the left of the cup for a tap in.

Vardon must have had some experience at snooker or pool, for he also recommended the “follow through” negotiation of a stymie. If you had a dead stymie with the offending ball fairly close to the hole, use your putter and strike your ball hard and high above center to give it over spin; the (hopeful) result is that the offending ball will be knocked over the hole and your ball, instead of stopping after striking the offending ball, will roll into the cup.

Find a pool table and practice putting a bit of “English” on the cue ball. Hit low on the cue ball and it will stop after striking another ball. Hit it high and when it hits the other ball, the cue ball will continue to roll forward.

Vardon recommended practicing all the stymie shots on the practice green. Three-time winner of the British Ladies’ Open Championship Cecil Leitch noted, “The majority of the bad results which follow an attempt to loft a stymie are caused by the player taking her eye off the ball and hurrying the stroke. The loft on the club is quite sufficient to raise the ball. The club should not be gripped too tightly for this shot. Occasional practice, even on a carpet, will give a player confidence to play this shot when called upon to do so in a match.”

Henry Longhurst had a similar thought suggesting the use of a “blaster” or sand wedge and almost putting your ball over the stymie using the weight on the bottom of the club to get your ball in the air.

James Braid recommended pitching over the offending ball with a lofted club and keeping the club head low so it would not dig into the green. “Generally,” Braid commented, “if the club is taken through easily and cleanly, all will be well; but it is on this point that the confidence of the player most frequently fails, and the shot is foozled and the ball knocked hard up against the other – perhaps even sending it into the hole – because the man jerks and hesitates with his club. The confident follow through will make the shot.”

One has to wonder what the keeper of the green thought about practicing a stymie pitch on the putting green. It’s one thing when watching James Braid smoothly stroke his lofted club on the putting surface and not ruff the green, but what about the average player attempting the same?

For negotiation of the partial stymie, Braid recommended a cut putt off the toe of the putter if going around the stymie ball from the left, and closing or hooding the putter face to go around the stymie ball from the right, again hitting off the toe, causing a hooked putt.

With the British in favor of the stymie and the Americans a little less so, there were a few events that turned public opinion, albeit over several years.

In his Grand Slam year, 1930, Bob Jones played Cyril Tolley in the second round of the British Amateur at St. Andrews and they were all square at the end of the 18th, sending the match to sudden death. Jones beat Tolley with a stymie on the 19th, although the fault lay with Tolley with a poor approach to the green.

Six years later, Johnny Fischer [the author’s father] met Scotland’s Jack McLean in the 36-hole finals of the U.S. Amateur at Garden City GC. McLean came to the 34th hole of the match one-up and looked headed to a win. Fischer’s third shot was on the green just closer to the hole than McLean who lay two just ten feet past the hole.

Bob Jones was following the match and reported, “I was standing with Grantland Rice in the gallery behind the green. I think we both appreciated the possibilities in the situation. Obviously, it was a time for conservative play by McLean. The wise play here was to sneak his ball down as close as possible to the hole, leaving Fischer the job of holing his putt to avoid being two down with two to play. A good putt here would make a punishing stymie impossible.

“I was horrified to see McLean going boldly for the putt on that keen green. The ball overran by more than a yard – and Fischer stymied him.

“Still trying to win the hole, McLean attempted to pitch from the dangerous distance. I just knew he was going to knock Fischer’s ball in for the win that would have squared the match. Fortunately McLean made overly certain that this would not happen, but he had to hole a four-footer to save a half. I have never experienced so many chills and thrills in so short a time.

“This hole cost McLean the championship. They halved the thirty-fifth in beautiful birdie fours, but Fischer holed a great putt to win the thirty-sixth, and won out at the first extra hole.”

The final straw for the stymie seemed to come at the last round of the 1951 English Close Amateur Championship at Hunstanton between Mr. G.P Roberts and Mr. H. Bennet with the match all square at the end of the 36th. The next two holes were halved, but Roberts lost on the 39th with a hopeless stymie.

Perhaps the stymie was as good a way as any to decide a drawn battle, but the opinion in England turned against the stymie at this point.

The following year, 1952, the USGA and the R&A banned the stymie.