By George Petro

Today is July 14, 2021, and the Open Championship is about to be contested at Royal St George’s in the southeast of England for the 15th time since 1894. In 1949 the winner was “Bobby” Locke, who would win three more Opens in 1950, 1952 and 1957 and ensure his induction into the hall of fame. Locke’s victory in ’49 was no surprise, with the bookmakers having laid him down as the strong 6:1 favorite, but a fateful uncertainty about the rules of golf cast a shadow of uncertainty on the outcome.

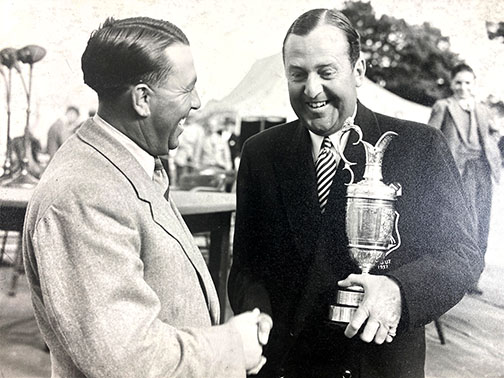

Locke and Harry Bradshaw of Ireland tied for the lead after 72 holes, ensuring a 36-hold playoff, as was the rule of the day. Bradshaw was a tough competitor, concluding his professional resume with 10 victories in the Irish PGA Championship, two wins of the Irish Open, and three Ryder Cup appearances.

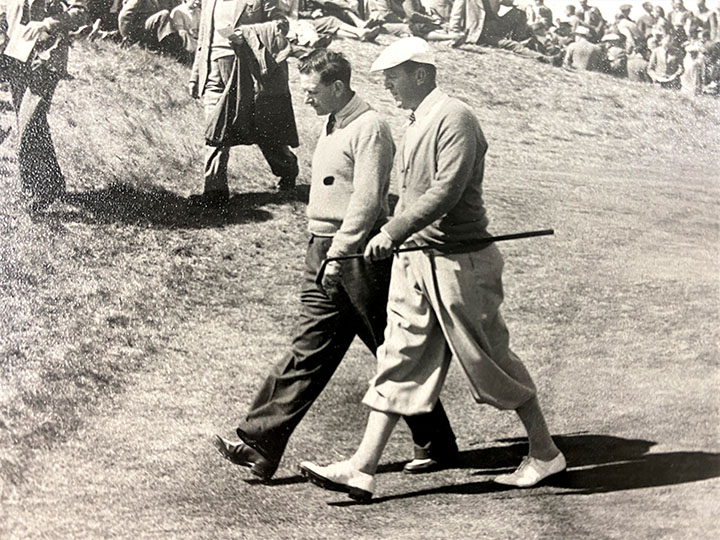

On the Tuesday and Wednesday of Championship week, 18-hole qualifying rounds amongst 224 contestants were completed respectively at nearby Royal Cinque Ports and Royal St. George’s with Bradshaw scoring 72-67 for 139 and Locke 69-71 for 140 as the two lowest qualifiers. Ninety-six qualified for 36 holes of the actual tournament at St. George’s on Thursday and 31 made the cut for the final 36 holes on Friday. But it was an incident on the par four fifth hole during the second round on Thursday afternoon that set the stage.

In one of the most bizarre incidents in Open history, on that hole Bradshaw had his drive come to rest within the jagged remains of a broken glass bottle standing upright adjacent to the fairway. Reluctant to take relief and risk disqualification, and without any referees nearby, he closed his eyes and struck a blow with his wedge. Emerging from the flying glass the ball traveled but 25 yards. His double bogey six led to a 77 for the round and a tie with Locke at 283, then the lowest four-round score in Open history. The stage was set for the 36-hole playoff on Saturday which Locke dominated from the beginning. His blistering first round 67 followed by a 68 bettered Bradshaw by 12 shots.

In an interview years later, Bradshaw reflected that he was right to play the ball from the bottle as he did, but that he also should have dropped and played another, recording both scores and letting the committee decide the eventual score for the hole. In 1949, Rule 24 (now Rule 15) regarding moveable and immoveable objects was then admittedly ambiguous with the subsequent rules clearly allowing a free drop.

What might have been for Bradshaw.

While the winner’s take was only 300 pounds, Locke figured that that his win in a Major was worth at least 25,000 pounds in eventual endorsements and appearance fees. Noteworthy is that Bradshaw bested Locke by one stroke to win the Irish Open just three weeks later.

As an aside, young Arthur D’Arcy Locke was nicknamed “Bobby,” by his father who idolized Bobby Jones.

After Hogan’s Open championship win in 1953, Peter Thomson edged out Locke by a single stroke in 1954 and also went on to win in ’55 and ’56. Thomson was denied four in a row in 1957 at St. Andrews when Locke prevailed but, not without another controversy. On his finishing hole Locke had four feet for birdie, marking his ball a putter-head to the side to clear the line for playing partner Bruce Crampton who was away, but Locke forgot to properly replace his ball and made the birdie for a three-shot victory over Thomson. Only later was the error pointed out to the R&A committee who decided that no significant advantage had been gained and the victory stood.

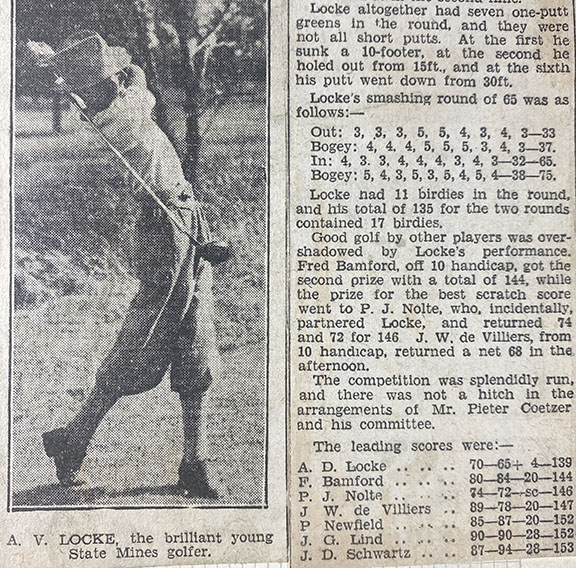

In less than a three-year period after the war, Locke played in 59 tournaments in America, winning 11 times, with 10 seconds, eight thirds and five fourth-place finishes. His unconventional style included massive hooks that still found fairways and greens, especially enviable putting, and a penchant for slow play that irked many of the American pros. Locke chose to remain in Britain following his 1949 Open win, snubbing tournaments he had committed to playing in the U.S. As a result, he was banned from the American tour. Although the ban was lifted in 1951, it discouraged his subsequent participation there. Two years after his 1957 Open victory, he had a severe automobile accident with injuries that affected his play though score cards from his personal scrapbooks include rounds in the mid 60s well into his later years. An early page from his scrapbooks shows the trim 16-year-old in knickers and fedora while shooting 70 – 65 (a course record) in a local tournament shortly before his numerous national South African victories. Even at that time he was noted to be an exceptional putter.

Locke’s numerous prizes and personal items went to auction at a Christie’s Auction in London during Open week in 1993 when Greg Norman won at Royal St. George’s.

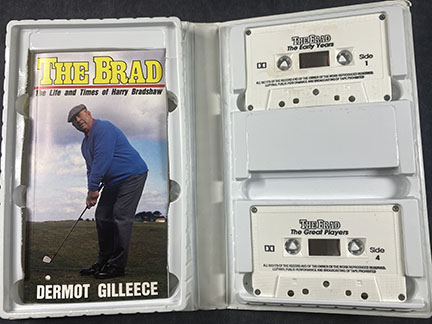

Bradshaw, known as “The Brad,” was a colorful character and storyteller. A double cassette tape, shown below, of an immensely entertaining interview with him is well worth the search. In it he tells the back story of many tournaments, his favorite courses in Ireland, his relationships with other greats of his era and experiences teaching members at his club. He recounts a moment that changed his golfing life when experimenting with his grip, he discovered that by changing his usual Vardon overlap with the right little finger on top of the left index knuckle, he increased the overlap to include the last three fingers of his right hand over the left fingers so that only the right index finger and thumb touched the grip. His long troublesome hook was gone. He turned to the skies and pronounced that this would be his baby for life and it certainly served him well.