A Random Golf Footnote from

John W. Fischer III

(Editor’s note: GHS member John Fischer III is an accomplished golf writer whose occasional ‘Random Golf Footnotes’ are sent to an established mail list of golf history enthusiasts. He is a long-time member of the Cincinnati Country Club where Otto Hackbarth was the golf professional for many decades. Mr. Fischer is also a valued contributor to The Golf magazine of the GHS.)

Otto Hackbarth is not a name which comes to mind in connection with American golf in the first half of the 20th century, but he ranks high in achievements as an early golf professional who always held a position at a golf club.

Many early professionals in the United States were transplants from Scotland taking advantage of employment opportunities as golf began a rapid growth across the country. Otto Gustave Albert Hackbarth was of German ancestry born in 1886 in Wisconsin. He and his three brothers started out as caddies, and all became golf professionals. Otto worked as a professional at Oconomowoc Golf Club but also had a mind to play tournament golf, and in 1903 entered the Western Open held at the nearby Milwaukee Country Club. He played quite well, finishing sixth or, as The Chicago Tribune reported, as low “homebred player…[showing] that good golf is not

altogether dependent on ancestry.”

Otto went on to hold two head professional posts in St. Louis, one at The Field Club, later renamed Bellerive Country Club, and the other at Westwood Country Club, before moving to Hinsdale Golf Club outside Chicago in 1911. Otto then accepted the head professional position in 1916 at the Cincinnati Golf Club, now the Cincinnati Country Club, where he would remain until the spring of 1951 when he retired.

His club jobs were normal, but not glamorous. He sold balls and clubs from his shop and planned and supervised club golfing events.

He also made golf clubs for the members which was an exacting undertaking. At the beginning of his career, Otto had to take hickory shafts, which came as rectangular rods an inch square, shape them using a plane, then a scraper and finally sandpaper. Shafts had to then be stained and varnished. Heads for the irons were forged by manufacturers and attached by the local professional to the shaft and then leather strips had to be wrapped on the end of the shaft to form a grip. Later on, shafts were made on a lathe and were sold to professionals for final finishing.

Heads for the woods arrived as a roughly shaped block of wood which had to be styled by hand, including the proper loft for the driver, brassie (2-wood), spoon (3-wood) and cleek (4-wood).

Making a “set” of clubs for play was time consuming, but in the early days golfers generally purchased clubs one at a time by looks or feel. The process was something like buy, try, discard and replace when a better club came along. This provided club pros a stream of business, along with the continuing need for professional maintenance and repair of hickory shafted clubs.

Otto stamped his name on the back of the irons and on top of the woods he produced, frequently using “Otto Hackbarth, Golf Expert.” The term “Golf Expert” was also used by the press to describe Hackbarth; it’s not clear if the term was picked up by the press after seeing his clubs or whether Otto took it from the newspapers and applied it the clubs he made. Regardless, he was generally acknowledged as a golf expert.

Otto taught members to use a rhythmic swing, to swing the club head rather than slug the ball. His students won two men’s city titles and one women’s city championship.

Otto had a few endearing quirks remembered by golfers who knew him. He was known to play in the rain wearing a full length raincoat and in the autumn carried a rake in his bag to locate balls that disappeared under the leaves. On one occasion Otto made a hole-in-one on a long par-3 at Cincinnati. He got a shovel from the grounds crew, carefully dug out the cup with his ball inside and the pin in place, and took it all back to his pro shop in a wheelbarrow, where it was on display.

In one city open championship Otto took an array of clubs, specialty irons, a short shafted driver, a lofter, an approaching putter and several left-handed clubs — just in case. There were so many clubs he needed two golf bags and two caddies.

Hackbarth studied the game and knew the strong and weak points of clubs from his skill at club making. If there was a weak point in his game it was his putting. Otto designed a new style putter which he was convinced would improve his putting. He manufactured his new putter and it began to develop a following. In 1914, Otto received a United States patent for his putter which became known as the “Hackbarth Putter.”

The putter had a bifurcated hosel with one prong attached to the toe and the other to the heel to limit rotation of the putter face. The head was the same on both sides so the putter could be used both right handed and left handed. The shaft was short because of the long hosel, and there was a strip of copper or lead inserted in the cast aluminum head to add some weight.

The August, 1910 Golfers Magazine noted that “Otto G. Hackbarth, professional at the Westwood Country Club, St. Louis, has invented a new putter of peculiar design with which he has been doing remarkably accurate work on the greens. It is modeled after the center shafted idea and he claims this prevents the club from turning when the ball is struck, with the result that the ball rolls with an over spin, hugging the ground and going perfectly straight for the hole.”

The Hackbarth Putter was well received, and several notable people used it, including Chick Evans, who won both the 1916 U.S. Open and the U.S. Amateur, baseball great Babe Ruth who was an avid golfer and putted left-handed, President Warren Harding and John D. Rockefeller.

With a strong following for the Hackbarth Putter, Otto was on his way for recognition of his design and some extra cash. The putter seemed to live up to its promises of keeping the club head square at impact. But it all came tumbling down. The USGA declared the Hackbarth Putter to be nonconforming under the Rules of Golf because of the split hosel. Sales ceased and today the Hackbarth Putter is only known to golf historians and collectors of golf memorabilia.

Otto was understandably discouraged, but went on with his career. From the beginning, Otto played in tournaments, most of which were played on weekdays so the professionals could be back in their shops tending to the members on the weekend.

Otto was a figure in the major tournaments of his time. He finished fourth in the Western Open three times, and played in 14 U.S. Open Championships from 1904 to 1924. His best finish in the U.S. Open was in 1912 when he finished tied for seventh place, winning $45 in prize money. Otto won several regional events including the Chicago PGA, the Ohio Open, which he won twice, the Gem City Open, the Greater Cincinnati PGA and the Queen City Open. In 1935, Otto made national news in a pro-am tournament held annually at The Camargo Club outside Cincinnati the day before qualifying rounds for the U.S. Amateur when a number of top amateurs would be present. Otto and his partner, Johnny Fischer, returned a best ball score of 59, which included a hole-in-one with a 2-iron by Otto on the 173 yard par-3 fifth hole. Their

card was 28-31=59, with no bogeys; Fischer scored 66 on his own card and Otto a 67, a good example of partners being able to “ham and egg” their scorecard. The round was written up in newspapers around the country and in The American Golfer magazine, and Otto frequently referred to it as his most memorable event. Otto helped the publicity by making sure copies of the newspaper reports got to golf magazines.

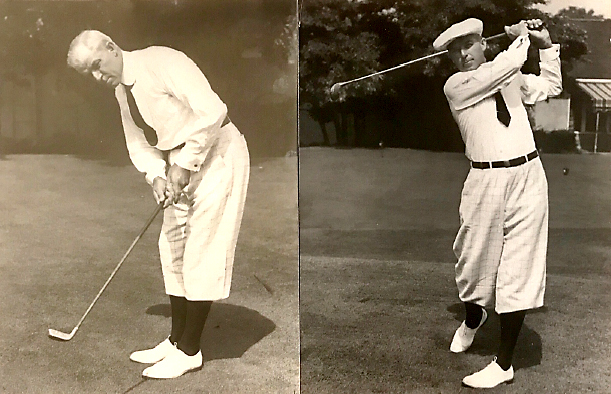

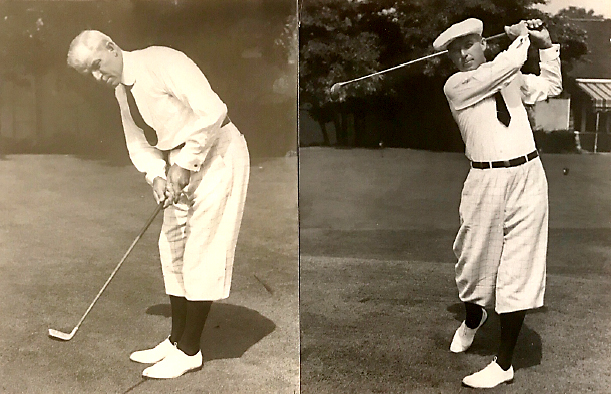

Otto was described as having “cannon-like drives,” hitting them as far as 280 yards. He used a driver with a 46 inch shaft, as opposed to the normal 43 inches, to allow for his 6’2” height. He had a slight “loop” in his swing, a result of taking the club back slightly outside and then dropping the club into plane. Otto had strong hands and forearms and gave the ball a good swat.

In the 1939 Gem City Open, Norm Butler, Otto’s playing partner, said of Otto, “sometimes he’d pick a club that to me would be definitely wrong, but he always proved he picked the right one. Take the way he played the short No. 4 hole Monday. I used a 7-iron and was hole high. Otto watched me hit and then picked out a 5-iron. He half-hit the ball, cutting it into the wind, and it was ‘stoney’ for a deuce. If you’ll watch fellows like Otto, you’ll find they’ll take a 3- or 4-iron and play a fade or a slight hook rather than hit a 5-iron shot straight.”

With Otto, everything was thought out. It wasn’t how far Otto could hit a club, it was how. Should he hit a fade, or a draw, carry the green or run up? His course management was legendary and it was said newer players could improve their scores just by following Otto and studying the way approached a hole and the shots required to get the best score. No shot was hit aimlessly, each with a specific target and a planned ball flight.

Hackbarth held the course record of 62 at his home course, Cincinnati Country Club. In 1938, Bob Jones played a match with Otto and two others at Cincinnati. Jones was playing quite well that afternoon and had two putts for a 61 at the 18th which would have broken Otto’s record. The story goes that Jones purposely three-putted so as not to break his friend’s record, a story confirmed by the daughter of one of the members of the foursome who watched the match. Otto was always proud that he and “Emperor Jones” shared the course record.

While the story sounds too good to be true, Walter Hagen said that whenever he played an exhibition he would check to see who held the course record. If the club pro held the record, Hagen would be careful not to break it. That always increased the image of the club pro which Hagen thought was good for the game.

In 1937, the PGA of America decided to hold a national event for senior golfers. Bob Jones thought the idea was a good one and immediately volunteered to host the tournament at Augusta National Golf Club. In the early days before The Masters gained the status it has today, Jones thought holding a second national event would improve the reputation of the course. Augusta National member Alfred S. Bourne donated the trophy, a true behemoth, 42 inches tall and weighing in at a hefty 36 pounds of sterling silver which was fittingly named the “Alfred S. Bourne Trophy.” The first National PGA Senior Championship was won that fall by Jock Hutchinson, who held the 1920 British Open, the 1921 PGA Championship and the 1923 Western Open titles. Alfred Bourne stepped up to pay the entire bar bill for all the contestants and the tournament was a hit with senior golfers from the start.

The next year, with miserable rainy weather at Augusta causing the cancellation of one round, and shortening the tournament to 36 holes, Otto Hackbarth was tied with Freddie McLeod, the 1908 U.S. Open Champion, at the end of regulation play, but lost in an 18-hole playoff by two strokes.

Because of the weather conditions in 1938, it was decided to move the tournament from Augusta National to the Bobby Jones Golf Course, a Donald Ross design in Sarasota, Fla., and the date was moved to January, so there was no 1939 tournament. In 1940, Otto was again tied for the lead at the end of regulation play, this time with Jock Hutchinson who had won the inaugural 1937 PGA Senior Open. Each had posted 146 for 36 holes.

An 18-hole playoff was scheduled for the following day, and both Hackbarth and Hutchinson posted rounds of 74. Still tied, a second 18-hole playoff gave Otto the championship with a 74 to Hutchinson’s 75. Victory came at the last hole of the playoff when Hutchinson shanked his approach shot and bogeyed the 72nd hole while Hackbarth two-putted for his par. Otto had won his national championship, and the Bourne trophy was his to keep for the year.

The 36-hole playoff between Hackbarth and Hutchinson in 1940 was the longest play off in PGA history and remains so today.

Otto retired as professional at Cincinnati in 1951 at the suggestion of his doctor. However, he kept playing golf at Cincinnati and frequently entered through a special gate at the far end of the course to practice which became known as “Otto’s Gate.” Only he and the greenskeeper had the key to the gate. That part of the course was more private and Otto could hit balls without interference. He kept his game in shape and at age 75 went around the Cincinnati course in 69, beating his age by six strokes.

Otto lived through the development of golf from hickory to steel, from handmade clubs to mass produced clubs, high-top hobnailed shoes to shoes made solely for golf, from the early rubber core Haskell golf ball to the age of the Surlyn covered ball, and learned to adapt his game as equipment changed. He died in 1967, the year the Ping putter was introduced and, interestingly, there are a lot of similarities between the Hackbarth Putter and the Ping, not the least of which is the designs were based on scientific principles.

And what did those changes do to the game during Otto’s competitive career? A comparison of Otto’s and Jock Hutchinson’s scores in the 1940 Senior PGA compared to another national tournament in which they both played, the 1908 U.S. Open held at Myopia Hunt Club, is instructive. Freddie McLeod won the Open in 1908 with a score of 322 for 72 holes. Hutchinson scored 82-84-87-85=338 and Hackbarth, 90-92-84-92=358.

In 1940, 32 years later, at the National PGA Senior Open, Otto had 294 for 72 holes, including the 36 playoff holes, and Hutchinson had 295. Otto was 64 strokes lower than in 1908 and Hutchinson was 43 strokes lower. Otto’s 294 was better than McLeod’s winning score of 322 at Myopia by 28 strokes.

Did Hackbarth and Hutchinson play better golf as seniors than they did in their prime? No, of course not. The different results are attributable to better clubs and balls, and greatly improved course conditions. It seems some things never change.