By David Moore

In the coming days, the elite professional golfers will be descending upon Pittsford, N.Y. to compete in the 105th PGA Championship at Oak Hill Country Club, May 18-21, 2023. The historic Oak Hill was once called, “the best, fairest, and toughest championship golf course” by four-time major champion Ernie Els, and it looks to stay true to the statement by showing off its recently renovated East Course during the championship.

The crown jewel in the region, Oak Hill is just a couple years away from celebrating its 125th anniversary. Over the course of its life, it has hosted 11 national championships (a dozen after this year’s PGA) – 3 PGA Championships, 3 U.S. Opens, 2 U.S. Amateurs, 2 Senior PGA Championships and the 1984 U.S. Senior Open – along with the 1995 Ryder Cup. The highly regarded Donald Ross design has ranked in the top 25 courses in Golf Digest’s Top 100 U.S. Courses list, including a rank of 20th in 2021-22.

As the golf world once again descends on the Rochester suburb, it is a wonderful time to step back and look at the illustrious history of Oak Hill and why it is regarded as a pillar of major championship golf in the United States.

The Founding

Golf was spreading across the United States at the turn of the 20th Century, and Rochester, N.Y. was not immune. In the fall of 1901, a group of 25 men came together to discuss the creation of a golf club for the city. After some deliberation, the group decided to venture forth, and on Oct. 2, 1901, they leased an 85-acre plot of land along the Genesee River. Oak Hill Country Club was officially established.

By the time the course was ready for play in the spring of 1902, Oak Hill had already found over 100 members. The original initial fee was $25 (nearly $900 in 2023) with an additional $5 fee for each person attached to the membership. Annual dues started at $20 (roughly $700 in 2023), which included access to the golf course, dinner and club functions, access to the river for watersports, and overall good ‘ol fashioned fun.

To this day, the designer of the original nine holes at Oak Hill is unknown. Like most courses of this era, there are likely two options on the origins. The first, a Scottish pro likely laid out the course and gave lessons, but his name was lost to time as such early professionals, typically nomadic, only stayed in one place for a year at most. The other option is that one of the Club’s accomplished players – and Oak Hill had a couple of candidates – laid out the course with a group of members.

Regardless of the creator, the golf course proved to be quite popular amongst the Rochester faithful, though the accounting books would say the opposite. Oak Hill was becoming an institution in Rochester, and the membership continued to pour money into the club. For most of the Club’s first two decades, the accounting books showed red figures, but that didn’t dissuade them. They soldiered on.

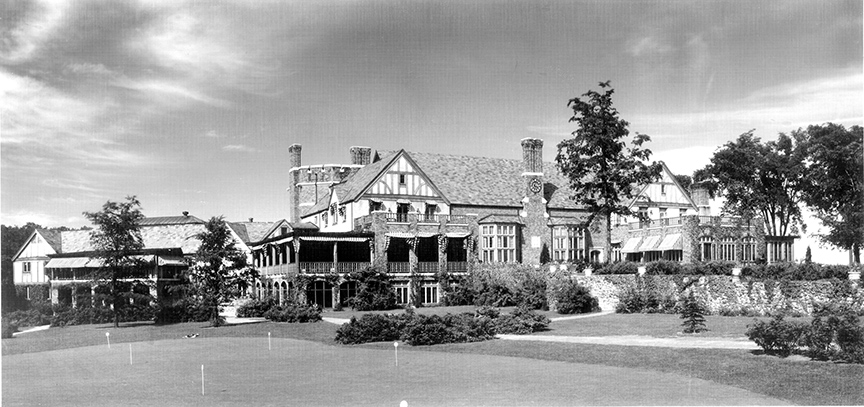

Proof that red in the ledger meant little to the club in the early years can be seen in two major additions around 1910 – the creation of a second nine holes and a new clubhouse. The clubhouse proved to be a big expense, costing nearly $70,000 to create, but increased initiation fees, dues, and as assessment financed most of the project. As for the golf course, like the original nine holes, it is unknown who the architect is. According to Club Historian Fred Beltz, a Rochester newspaper notes that “Donald Ross of Boston” says there is room for another nine holes. There is no concrete proof Ross designed this second nine holes, but if he did, it would be his first work in the state of New York. Beltz also notes that Walter Travis offered to design the course, but again, there is no proof to give him credit.

By World War I, especially in the years immediately following, golf grew exponentially in popularity. A major reason for the uptick, especially in Rochester, was a native son who, in 1914, became just the third American to win the United States Open Championship – none other than Walter Hagen. “The Haig” as he’d affectionately be known for the remainder of his life, would go on to win 11 major championships, including four consecutive PGA Championships (1924-27), and became the first American-born winner of the Open Championship (1922).

With Hagen’s popularity helping to drive the sport and the age of affluence about to take hold in the post-war years, Oak Hill was on top of the world heading into the “Roaring 20s.” Then an offer came about that seemed just too good to be true, but one that would reshape the history of the Club.

Eastman’s Offer and Move to Pittsford

While Rochester’s industry grew on the back of the railroad and shipping industry, the city’s largest employer was none other than the Eastman Kodak Company, run by the “father of modern photography” George Eastman. As one of the nation’s foremost philanthropists, Eastman left a mark that can still be felt throughout the City of Rochester to this day, nearly 90 years after he tragically took his own life.

One of Eastman’s biggest philanthropic works directly affected Oak Hill. In the early 1920s, Eastman bequeathed a sizable sum of money to the University of Rochester, originally located on Prince Street in downtown Rochester. The money was to fund a new medical center and school of music for the university if proper land could be found to house the new institutions. After much searching, the university settled on an 85-acre track along the Genesee River, home of Oak Hill Country Club.

University President Rush Rhees opened talks with the club, hoping to procure the land. The offer that Rhees and Eastman proposed to the Club was 355 acres of farmland in Pittsford, a suburb of Rochester, as well as the funding of two 18-hole golf courses and a brand new, Tudor-style clubhouse, roughly $360,000 total (about $6.35 million in 2023). While some of the membership did not want to accept the offer, an agreement was struck, and Oak Hill officially gave up the river-side property. While the deal was struck in 1924, the Club would not officially leave for Pittsford until 1926.

The Architects – Donald Ross and Dr. John Williams

Looking back on what made Oak Hill what it is today, you can safely say two architects are responsible. The first was Donald J. Ross of Pinehurst. A native of Dornoch, Scotland, Ross apprenticed under Old Tom Morris at St. Andrews before becoming the pro and greenkeeper at his hometown links, now known as Royal Dornoch. In 1899, he was invited to the United States by Harvard professor Robert Wilson, who set Ross up at Boston’s Oakley Golf Club. There, Ross split his time between New England and Pinehurst, North Carolina, where he was engaged by James Tufts in 1900 to build the golf courses of the now famous Pinehurst Resort.

For the next 40 years, Donald Ross built a career that made him one of, if not the, most renowned golf course architects in American golf history. Among his notable designs are Pinehurst No. 2, Seminole, Oakland Hills, and Inverness.

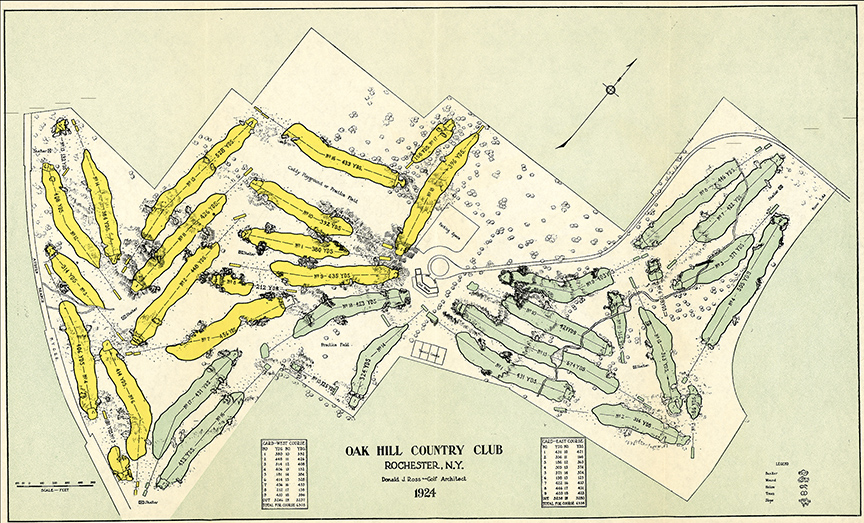

When it came time to design their new 36-hole facility in Pittsford, Oak Hill immediately turned to Ross. As mentioned previously, there may have been a connection to Ross at the old location, but there is no concrete proof to show that Ross designed that second nine along the Genesee River. However, he took the opportunity afforded him in 1924 to design two wonderful courses at the new property.

Oak Hill’s East and West courses were laid out and dug out of the dirt during the 1924 season. They were allowed to mature in 1925, meaning the Club did not officially open in Pittsford until the 1926 season. When all was said and done, Ross’ work cost the club about $165,000 (about $2.9 million in 2023) for the two designs, irrigation system, and other costs.

The land that Ross shaped into the East and West courses had, after nearly a century of farming, become barren when it was purchased by the Club in 1924. Only a few trees were on the sprawling property.

If Ross is the architect who designed the golf course, then Dr. John Williams is the man who “beautified” it. John Ralston Williams was born in Ontario, Canada in 1874, but grew up in Rochester once his family moved there during his teenage years. He graduated top of his class from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1903 and is known for being the first American doctor to administer insulin as a treatment for diabetes in the United States.

Williams, a long-time member of Oak Hill, took an interest in trees and became a self-taught arborist. His research showed that several species of trees would thrive in Rochester’s climate, but the mighty oak would stand above all. He planted trees in his back yard from acorns and eventually transplanted them along the fairways at the Club.

When all was said and done, some 30,000 to 75,000 trees were planted on the property by Dr. Williams. No official number is available, though Williams told many people he stopped counting at 30,000. When Oak Hill member Bill Westerfeld told CBS commentators this fact during a tour prior to the 2003 PGA, David Feherty responded, “Boy, he must have really loved to drink coffee!”

A grove of Dr. Williams’ trees surrounding the 13th green created a natural amphitheater that lends more gravitas to the Club’s signature hole. It was there among those trees in 1956 that the “Hill of Fame” was founded. Many of the trees in this area display a bronze plaque, honoring someone important to the Club’s illustrious history. The good doctor believed “a living tree is a much better monument than a piece of granite.” Among those honored upon this hill are American presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Gerald Ford, champions at the Club such as Nicklaus, Hogan, Trevino, and Strange, and other Club figures such as William Chapin, William Reeves and Williams himself.

The combined efforts of Donald Ross and Dr. Williams make Oak Hill what it is – a major championship caliber golf course with a breathtaking parkland view.

A Championship Caliber Course

Almost immediately following its creation, the East Course at Oak Hill was recognized as something special. The members took to the course immediately and offered it to the New York State Golf Association for their 1927 Amateur Championship, which was won by Rochester native Arthur Yates. The course proved a hit, and next the membership looked to get the world’s best traversing its fairways.

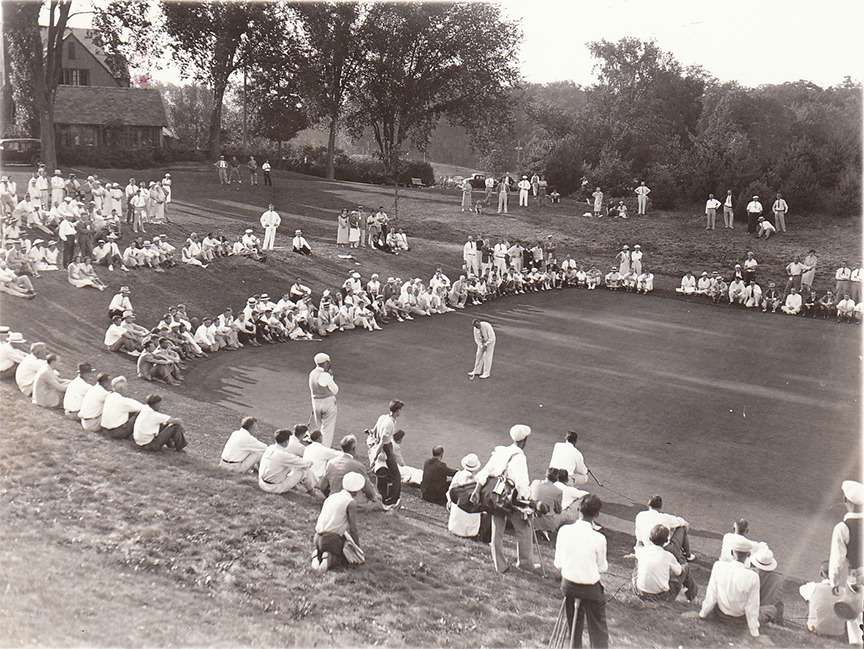

The biggest names in golf first played the fabled East Course in 1934. To celebrate the centennial of the city, and the 20th anniversary of Walter Hagen’s U.S. Open triumph, Oak Hill hosted the Walter Hagen Centennial Open golf tournament. The event featured a field comprised of the native son, and all his buddies, including “Lighthorse” Harry Cooper, Paul Runyan, and Denny Shute. The eventual winner was two-time PGA Champion Leo Diegel, who defeated the man of honor by 12 shots. Many hoped the top pros would make the event an annual thing, but the membership would have to wait seven years for their next big event.

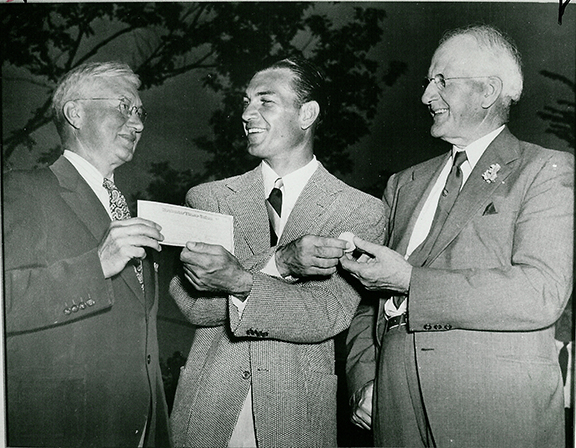

In 1941, Oak Hill member, and founder of media empire Gannett Company, Frank Gannett posted a $5,000 purse and the Times-Union Open, named after Rochester’s evening newspaper, came to the Club. The 1941 event featured a who’s who of professionals, including Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Gene Sarazen, Horton Smith, and Lloyd Mangrum. Sam Snead won the event, shooting 67-70-73-67 for 277, three-under par. Though Snead won, it was Ben Hogan who was smitten by the course, promising to return if the event was held in 1942.

Despite America’s entrance into the Second World War, the Times-Union Open returned to Oak Hill in August 1942. Ben Hogan remained a man of his word and returned to compete in the event before spending the next three seasons in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He truly had an eye for Oak Hill’s East Course as he fired an opening round 64, which would stand as the course record for the next 71 years. Hogan shot 68-72-74 over the final three rounds to claim the title by three shots over Craig Wood.

Oak Hill would have to wait until after World War II for its next event. When golf returned, it was in the form of a national championship. The first of six USGA Championships to date came in 1949, when the Club hosted the United States Amateur. Oklahoma native Charlie Coe made impressive work of a field that included the likes of Arnold Palmer and Frank Stranahan. Coe defeated future USGA President Bill Campbell in the semis 8 & 7, before taking down Texan Rufus King 11 & 10 to claim the Havemeyer Trophy.

The USGA returned in 1956 for the first U.S. Open Championship at the Club. Beforehand, some alterations to Ross’ original design were made at the behest of the USGA, with Robert Trent Jones Sr. completing the work. Though the Club and USGA were content with the work, four-time U.S. Open Champion Ben Hogan was not.

Quite complimentary of the East Course during the Times-Union Open days, Hogan noted that the changes made the course “the easiest course I’ve ever seen for a national open.” With the scar tissue of the previous year’s devastating playoff loss to Jack Fleck at Olympic still on everyone’s mind, Hogan opened play on the “easiest course” with a two-over, 72. He followed that up with rounds of 68 and another 72, heading into the final round a shot behind Dr. Cary Middlecoff. He finished the final round with an even-par, 70, but a missed 30-inch putt on the 71st hole cost him the Open. Middlecoff claimed the title as a result.

Twelve years later, the USGA returned to Oak Hill. This year, the course proved quite easy, as Lee Trevino showcased by shooting each of his four rounds in the 60s, a feat that had never happened in a prior U.S. Open. The “Merry Mex” earned his first career win, and first of six career major championships, by firing 69-68-69-69 around the East Course.

Why was the East Course so easy to play in 1968? Many attribute it to a disease that killed many of the Dutch Elm trees on the property, which resulted in their removal, allowing for more cavalier shot making. The USGA wondered if Oak Hill was worthy of another Open, and the Club brought in George and Tom Fazio to rework the course in the 1970s with the hope of securing another major championship. The Fazios drastically reworked the course, eliminating much of Ross’ original work, but severely toughening the golf course ahead of the 1980 PGA Championship.

Many at Oak Hill, Beltz included, believe that the 1980 PGA Championship was the most pivotal event held on the East Course. After the low scores during 1968 U.S. Open and the subsequent renovations by the Fazios, the Club needed confirmation that it still had the qualities worthy of a major championship venue, at the cost of losing much of Ross’ original design.

To their relief, and despite losing much of Ross’ work, the Fazio redesign proved to be of major championship caliber. After claiming the 1980 U.S. Open at Baltusrol a few months earlier, Jack Nicklaus marched across New York to claim the PGA at Oak Hill as well, his fifth and final PGA Championship of his career. The course proved to be more difficult for the mere mortals, as only Jack was able to traverse the newly renovated course under par for the week. He fired 70-69-66-69, six-under par, and seven shots ahead of second place Andy Bean at one-over.

The showing at the 1980 PGA brought the USGA back into the fold with the 1984 U.S. Senior Open Championship, which saw Miller Barber shockingly take down Arnold Palmer to claim the title. The 15th hole proved costly to the King’s chances, as he was long off the tee into the par-3 but recovered when his chip stopped mere inches from the hole. As he went to tap in, he somehow whiffed on the putt, and called the appropriate stroke on himself. Palmer made bogey. Barber was so flabbergasted by the events, he also bogeyed the hole, but steadied the ship to finish off Palmer and claim his second of five senior major championships.

Five years later, the U.S. Open returned to Oak Hill in what proved to be a historic week. On Friday, within a span of about two hours, four holes-in-one were made on the devilish par-3, sixth hole. Jerry Pate started it off and was followed by Nick Price a few groups later before Doug Weaver and Mark Wiebe added to the historic festivities. Each man hit a 7-iron into the 167-yard hole. At one point, the USGA considered replacing the official scorer on the hole, as they thought he’d cracked up by reporting all these holes-in-one. There had only been 17 total holes-in-one in the tournament’s 89-year history before that day.

The historic week continued thanks to Curtis Strange. The defending champion hoped to become the first since Ben Hogan to successfully defend his title. He shot an opening round 71 before proceeding to tie Hogan’s course record with a 64 in the second round, giving him a one-shot lead over Tom Kite. Strange fell back on moving day, firing a disappointing 73 to fall three shots back. Kite, who led Scott Simpson by a shot heading into Sunday, suffered a horrific day, which included a triple bogey at the fifth, and double bogeys at both the 13th and 15th. Strange opened play with 15 consecutive pars before finally making birdie at the 16th. He three-putted 18, but it was enough to hold on and match Hogan as a back-to-back U.S. Open Champion.

In 1995, Oak Hill played host to the Ryder Cup. The event saw the Europeans win in dramatic fashion over the Americans, with a final score of 14.5 to 13.5. The Americans performed well in the team portion of the event, heading into Sunday singles with a 9-7 advantage. Tom Lehman opened singles play with a huge win over Seve Ballesteros, but only three other Americans – Davis Love III, Corey Pavin and Phil Mickelson – were able to win their matches on this day. The Euros took 7.5 of 12 possible points from the Americans in singles, helping them secure just their second Ryder Cup win on American soil.

Three years later, the U.S. Amateur returned to Oak Hill. For the first time, both courses were on display, with qualifying rounds being played across both the East and West courses. Texan Hank Kuehne powered his way around the course, driving the ball to places no one could have considered before the tournament. For example, he completely cut the corner on the dogleg right, par-5 17th hole, having a mere pitching wedge in while most of his opponents played it as a three-shot hole. He would claim the Havemeyer Trophy, defeating Tom McKnight in the finals 2 & 1.

With the turn to the 21st century, the PGA returned to the Club in 2003, the first time since Nicklaus’ triumph in 1980. Many expected the likes of Tiger Woods or Ernie Els to claim the title, but it was little known Tennessee native Shaun Micheel who took home the Wanamaker. On the 72nd hole, he hit a 7-iron from 175 yards to kick-in range to cement his victory over Chad Campbell. To date, it is Micheel’s only PGA Tour win.

The Senior PGA Championship came to Oak Hill for the first time in 2008. American Jay Haas won the event, shooting seven-over par for the week in defeating Germany’s Bernhard Langer by a shot. Haas’ score proved to be the highest winning score in relation to par in tournament history, with the previous record being set by Sam Snead in 1970 (2-over par) at PGA National.

In 2013, the PGA returned to Oak Hill for the third time. Jim Furyk and Adam Scott jumped out to an early lead after the first round. In the second round, Jason Dufner set the course record, and tied the then-major championship scoring record, by firing a seven-under, 63. Dufner held a two-shot lead after 36 holes before entering the final round a shot behind Furyk. He fired a two-under, 68 on Sunday to win the event, atoning for a devastating PGA Championship loss just two years earlier.

Finally, to wrap up the 2010s, the Club hosted the 2019 Senior PGA Championship, just a couple months before launching a historic restoration. Scoring proved easier this time around for the seniors, with Ken Tanigawa shooting three-under par to win by a shot over Scott McCarron, 10 shots better than Jay Haas’ total in 2008.

Restoration

As we look ahead to the 2023 PGA Championship, Oak Hill will look different from its last hosting a decade ago. Josh Sens of Golf Magazine put it best in his preview,

“When play gets underway at the 2023 PGA Championships, the world’s best will get their first crack – and fans will get their first glimpse – of a Golden Age great with a grand legacy, where everything old is new again.”

Sens hits the nail on the head with his statement, as the Oak Hill of today is as close to Ross’ original design that the world has seen since Robert Trent Jones Sr. got his hands on the course ahead of the 1956 U.S. Open. Club historian Fred Beltz said this year will be as pivotal a championship as the 1980 edition because “the hope is the East Course will have a truly major championship feel, while also presenting a truly authentic Donald Ross designed course.” A distinguished pedigree, many felt, was sorely lacking after the Fazio renovation in 1980.

Ideas of restoration began in earnest in 2014. The Club’s Architectural Review Committee, a subsidiary of the Grounds Committee, began imagining the East Course reverting to its original Ross design. For the next several years, this group, along with architect Andrew Green and Oak Hill member and former PGA Tour winner Jeff Sluman, began drawing up plans and educating themselves and the membership on a true, authentic Ross restoration. The membership voted in favor of the work in 2017, and work began in the summer of 2019.

Green and his team’s work took Ross’ original drawings and tried to modernize them. Essentially, they took what Ross created, his bunkering, his mounds, etc., and brought them back into play for the modern player. Some bunkers were added, some taken away, other hazards were taken out and replaced with other Ross features, and some of Dr. Williams’ trees needed to be removed as well. They finished their work during the 2020 season.

A lot of focus will be on the stretch of holes comprising four, five and six. The fourth hole, which used to play as a relatively easy par-5, will likely turn into a difficult, three-shot par-5 for the upcoming championship, playing at nearly 620 yards. The new fifth hole replaces the old sixth hole, a nifty little par-3 that at one point was characterized as “putting a mustache on the Mona Lisa” after a previous renovation. The new sixth will mimic Ross’ original sixth hole, bringing a creek into play on both the tee shot and the approach shot while playing at around 500 yards.

On the back nine, the course’s signature hole, the par-5, 13th, also received an upgrade. The hole was stretched out another 30 yards, bringing the creek that bisects the fairway into play again. A pesky tree on the left side has been removed for those hitting their approach shot, and the green was completely rebuilt in a square shape to mimic Ross’ original drawings. Some other trees surrounding the green were removed as well, but fret not, the Hill of Fame has remained untouched. New bunkers on the 18th hole will make driving accuracy even more paramount, as the players try to close out the tournament on a difficult, 490-yard par-4.

Overall, what Green produced not only made the course a challenge for today’s player but invoked the spirit of what Donald Ross created over his four decades on the job. As Beltz stated, the hope of the membership is that the restoration Green undertook will not only keep the East Course a major championship masterpiece, but also return it to a true Donald Ross design.

Oak Hill Today

As Oak Hill Country Club approaches its 125th anniversary in 2026, and their centennial year on the Pittsford property that same season, it can look back on its illustrious history and be proud of its standing in the game of golf. Oak Hill, which didn’t start hosting national championships until the late 1940s, has hosted 11 national championships, with the 2023 PGA bringing the total to an even dozen. To date, it is the first and only club in the country to have hosted all six of the men’s traveling major championships – U.S. Amateur, U.S. Open, U.S. Senior Open, PGA Championship, Senior PGA Championship, and the Ryder Cup.

If Josh Sens’ description of the renovated East Course proves true, the “Golden Age great with a grand legacy, where everything old is new again,” Oak Hill will remain a pillar for major championship golf in the United States. The USGA is slated to return in 2027, bringing the U.S. Amateur to both courses, and if the PGA proves successful, it should not be long until the best players in the world descend upon the Western New York gem with regularity as they did in the last couple decades of the 20th Century.