Random Golf Footnotes by John Fischer III

The BMW Championship is being played this week (Aug. 27-30, 2020) at Olympia Fields Country Club outside Chicago as part of the FedEx Cup playoffs. Eighty-seven years ago, when the tournament was known as the Western Open, the focus was more on cops and killers at Olympia Fields than on golf

After the second day of the 1933 Western Open, the headline on the front page of the Chicago Sunday Tribune read, ARREST M’GURN AS HE GOLFS IN WESTERN OPEN. To learn that MacDonald Smith held the 36-hole lead at 1-under 139, the golfing public had to dig inside the paper.

“M’Gurn” was “Machine Gun” Jack McGurn, a lieutenant in Al Capone’s gang known colloquially as the Outfit who was suspected of killing 25 Outfit rivals. Despite his nickname, McGurn preferred a .38-caliber revolver or a .45 automatic pistol for his closeup dirty work. McGurn was so good with a handgun that he also became Capone’s personal bodyguard.

McGurn was believed to be the mastermind behind the infamous 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre when seven members of George “Bugs” Moran’s Northside gang were gunned down in a garage on Chicago’s Clark Street.

McGurn was a suspect, but he had an alibi; he’d spent St. Valentine’s Day with girlfriend Louise Rolfe at the Stevens Hotel in Room 1919A. Police found the room littered with newspaper articles about the massacre, but no charges ever were filed against McGurn or Rolfe, who was dubbed the “Blond Alibi” by the press.

Jack’s family had come to America from Sicily when he was a boy known as Vincenzo Gebardi. After his father died, his mother remarried a man named Angelo DeMory. As a teenager, Vincenzo became a boxer and used the nom de guerre Jack McGurn because he thought Irish boxers got better bouts and also didn’t attract attention from police. The name stuck for life.

Young Jack did fairly well as a boxer. He was short but very strong, having worked for a while as a stevedore on the docks. At 140 pounds, he was classified as a welterweight, punched above his weight and was known to be tough as a bare-fisted street fighter. His neighbors noticed that Jack always had a lot of money, even when he was not fighting in the ring, indicating he had hooked up with Capone at an early age.

Jack’s stepfather, DeMory, was a grocer who sold sugar to bootleggers for use in making liquor during Prohibition, and also made deliveries of the finished product to speakeasies and clubs. DeMory was killed by three men who’d described him as an unsuccessful “nickel and dime” man. His killers were Capone rivals. McGurn eventually was tasked with their killing, extracting revenge for the death of the man who helped raise him.

McGurn married his girlfriend, Louise, the Blond Alibi, and they lived the good life, moving to suburban Oak Park, driving fancy cars, wearing tailored clothes and partying at many of Chicago’s jazz clubs. McGurn was a suspect in many gangland killings, but he never was convicted of anything more than carrying a concealed weapon and served only probation. His weapon was a necessity of life; members of other gangs knew who he was and his reputation as a killer. When McGurn was picked up by the police, the Outfit’s lawyers got him released.

In his spare time, McGurn loved to play golf and became quite good at the game. He held part ownership in Evergreen Golf Course, a daily-fee operation in suburban Evergreen Park. It was known as an Outfit hangout and a place where big bets could result in the exchange of as much as $10,000, or about $150,000 in today’s money.

McGurn had a cherubic face and didn’t look like a typical gangster. He had a quick mind and a quick wit. When arrested, he played the victim’s role. He told the police and the media that he carried a gun because his stepfather was murdered, and his life had been threatened, both of which were true but gloss over the full truth. Rolfe, his girlfriend, loved to play the press and could be coy or sexy or burst into tears as necessary to gain sympathy for herself and McGurn.

But by 1932, things begin to change. Capone had been found guilty of federal income-tax evasion and was sentenced to 11 years in prison. Prohibition was nearing an end. The Outfit, headed by Frank Nitti, pursued gambling and laborunion infiltration as a way to make up for lost revenue. Nitti didn’t like McGurn, whose services were not as valuable as before.

McGurn hadn’t given up on crime and ran a bookie operation, but he decided to focus on his golf game. He spent more time going to Miami to play golf and worked on becoming a professional golfer. McGurn shot in the low 70s and played frequently with men of high social standing who enjoyed his company and his golf game, and liked to tell others that they played golf with this charming gangster. However, McGurn wasn’t invited into their social circles, and golf usually was played at public courses.

During the Capone years, the Outfit was flamboyant, but the modus operandi soon led the gang to keep a low profile and out of the public eye. Golf provided McGurn with a way to reduce his public persona. He was on the golf course, not in the newspaper. In July 1933, the Chicago Tribune reported that McGurn had been killed by a rival gang. The press was waiting at his Oak Park home for more information when McGurn pulled up. When he was told that his death was reported in the Tribune, McGurn replied, “Did you ever hear of a ghost shooting a 66?”

One month later, with his game honed by plenty of practice, McGurn decided to enter the Western Open, listing himself as the Evergreen professional under the name Vincent Gebhardi, a variation on his real name of Vincenzo Gebardi. This, he thought, would make him inconspicuous.

However, the Times newspaper of Munster, Ind., commented before the Western Open started, “We noticed this morning that “Vincent Gapardo, Evergreen” is entered in the Western…NEVER HEARD of a Gapardo, but there is a Vincent Gebardi whose newspaper name is “Machine Gun Jack” McGurn…BUT MAYBE the golf officials don’t want it mentioned in the papers.”

William Shoemaker, Chicago’s chief of detectives, was a golfer and, on the morning after the first round of the Western Open, he also saw the Gebhardi name in the list of scores. Shoemaker was sure that it was Jack McGurn, and he had good reason. McGurn had been arrested twice in Miami while playing golf. If you were looking for McGurn, a golf course was a good bet.

Chicago had just passed a law to treat individuals associated with crime as vagrants unless they could show legitimate income. Frank Loesch, head of the Chicago Crime Commission, had classified Jack McGurn as No. 4 on the Public Enemies List, and an arrest warrant was issued for McGurn.

It was decided to arrest McGurn at Olympia Fields on the second day of the tournament under the assumption that McGurn would be less likely to cause a disturbance or pull a gun from his bag in front of a large gallery, a questionable assumption in dealing with a man bearing the sobriquet “Machine Gun Jack.”

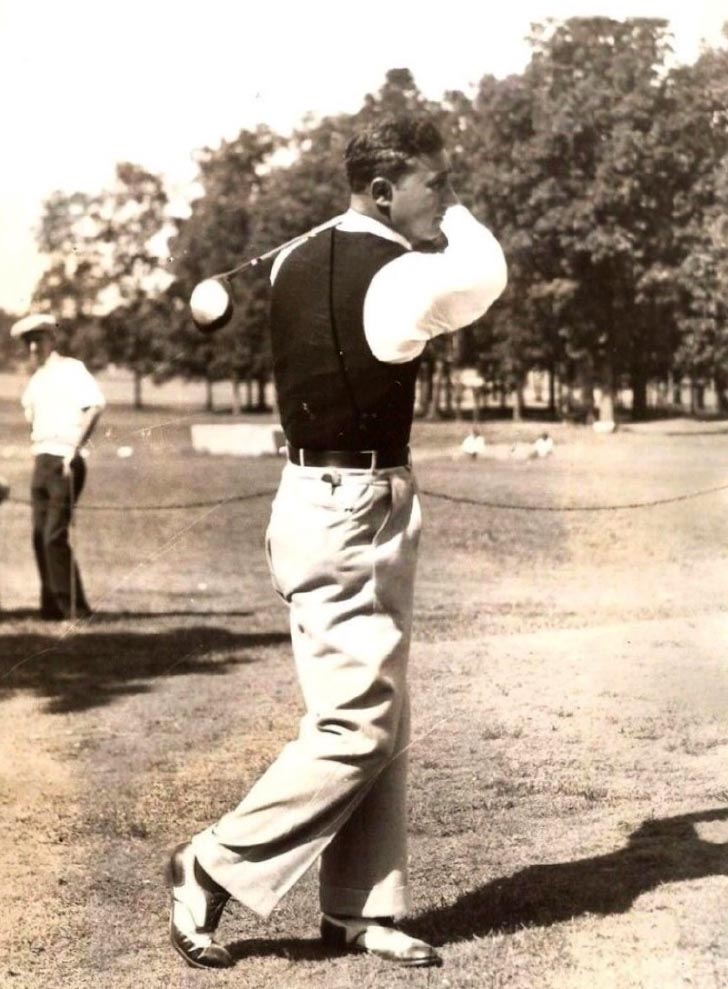

Five uniformed policemen and three plainclothes detectives led by Lt. Frank McGillan arrived at Olympia Fields looking for McGurn. The uniformed officers stayed around the 18th green trying to look inconspicuous while the plainclothesmen walked onto the course and found McGurn, tan and fit, wearing gray flannel trousers, white shirt and tie, and black and white golf shoes, lining up his putt on the seventh green.

After putting out, McGurn was approached by McGillan, who read the arrest warrant. McGurn remained calm, and when McGillan was finished, McGurn politely asked if he might finish his round. At this point, he was 1 under par for the day. McGillan agreed, thinking there was nowhere for McGurn to run.

McGurn’s playing competitor, professional Howard Holtman, appeared undisturbed, or perhaps dazed, when McGillan read the portion of the warrant which included “alias Machine Gun Jack McGurn.” Being from nearby Beecher, Ill., Holtman certainly knew his playing competitor by reputation.

Rolfe, the Blond Alibi, had been following him and was there when the arrest warrant was read. The newspapers described her as wearing “a tight white dress, white hat and anklet stockings.” She also sported a wedding ring, a threecarat diamond, and a nice tan. She was carrying a red leather purse, which the police searched for a weapon; there was nothing more than a compact and a bottle of perfume.

If everyone involved had been acting as though nothing unusual was going on, Mrs. “Machine Gun” wasn’t. She confronted McGillan, demanding to know, “Whose brilliant idea was this?” McGillan didn’t answer, shrugged his shoulders and walked on to the next tee with McGurn.

McGurn proceeded to double bogey the next hole and then took an 11. McGurn went after a photographer who’d been taking pictures while McGurn was putting, leading to a verbal row but no physical altercation.

At one point, it was reported that McGurn asked his caddie, “What do I use here?” To which the caddie is said to have replied, “Use your No. 1 lawyer, sir.” That exchange certainly was fabricated, but it made for good copy.

McGurn pulled his game together, but not enough to matter, shooting a second round 86 to go with an 83 in the first round. Holtman finished the round, posting a 91.

When the round was over, McGurn got testy with the press, threatening to bash a photographer’s head for trying to get a picture. Oddly, police let McGurn and his wife drive his car to the police station, with two policemen tucked into the rumble seat of his roadster.

McGurn addressed reporters at the police station, saying, “I was out playing golf, so they arrest me. Trying to suppress crime, hey? It’s the punks out pulling stickups who shoot the policemen. Why bother me? I haven’t done anything for a year. Just put down that I’m booked for carrying concealed ideas.”

McGurn spent the night in the Cook County Jail, but reporters got a chance to interview him, and he was furious. He’d been reading that Enid Wilson had shot a record score in qualifying for the U.S. Women’s Amateur being played at Chicago’s Exmoor Country Club. “Sure, she shot a 76,” McGurn said, “but this English girl didn’t have a bunch of bulls trailing her down the fairways and up onto the greens. That’s when my game cracked. The sight of the bulls got me all upset, and those photographers were blasting away while I putted.”

The powers at Olympia Fields weren’t happy, either, worrying that the club’s reputation might be tarnished. Member Michael Igoe, a former state representative and park board member who later would ascend to the Congress and a federal judgeship, fussed, “It wasn’t any credit to the police department to arrest McGurn on the golf course. If they knew he was entered, they should have arrested him before he started playing.”

McGurn was given a jury trial with Judge Thomas A. Green presiding. McGurn was found guilty under the vagrancy law and sentenced to six months in the workhouse. McGurn’s attorney was framing a motion regarding McGurn’s relationship with Judge Green, but the judge interrupted, “I know what you’re driving at. I was playing once at the Evergreen public-fee course with the manager and the professional. A fourth man joined and was introduced to me. That man was McGurn. It was purely a coincidence, and it might have happened to anyone on a golf course.” Later, the judge explained that he withdrew when he found out he was with McGurn. The judge didn’t recuse himself from the case, and never explained why he was playing at a known Outfit hangout.

McGurn never served his sentence. The Chicago vagrancy law was found unconstitutional by the Illinois Supreme Court, which held, “before liberty or property may be taken from someone, regardless of his reputation, there must be proof that he is in fact a habitual criminal.”

However, McGurn’s professional golf career was over. McGurn ran a restaurant and still was involved in gambling, but he no longer was part of the inner circle of the Outfit, and his financial resources dwindled.

On Valentine’s Day 1936, McGurn and two friends went bowling. His wife stayed home. Three men burst into the bowling alley, firing pistols into the air and shouting, “This is a stickup.” McGurn was shot in the back of his head with a .45- caliber pistol and died instantly. It was one hour and five minutes past Valentine’s Day. McGurn drank and talked too much about other mobsters and had become a liability. The 20 people who were in the bowling alley had a collective case of “Chicago amnesia”; no one saw anything. The killers left a Valentine’s Day card for McGurn at the reception desk. His killers never were found.

McGurn’s wife died at age 88 in 1995, maintaining to the end that her late husband wasn’t part of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. All she’d say was, “When you’re with Jack, you’re never bored.”