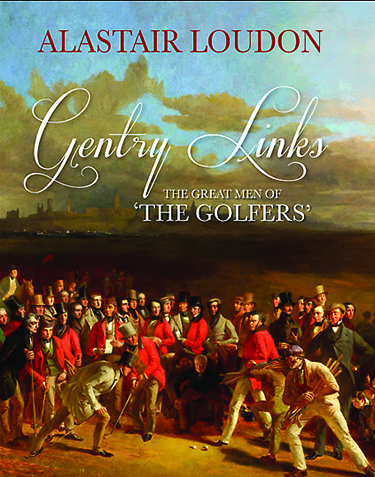

By Alastair Loudon

Published by gentrylinks.uk

Several editions – hardback, £45; paperback, £30; and 53 limited editions, one for each character in the painting, £295. 192 pages

Order at www.gentrylinks.uk

Reviewed by David Normoyle (The Golf, Summer 2019)

What a coup it would be if every member of every golf club, everywhere in the world, that displays a copy of Charles Lees’ The Golfers had his own copy of Alastair Loudon’s new assessment of that famous painting from 1847, Gentry Links: The Great Men of ‘The Golfers’.

How many times have we walked past a faded print of this grand golfing art and failed to give it a second glance or even ask who the people in the scene might be? Loudon, whose family roots ground him both in St. Andrews and the Royal & Ancient, has now given this painting more second glances than anyone in history, apart from the artist himself.

In setting out to establish a biography of every person identified in the painting, and even those who were not, Loudon attempts to weave together innumerable connections between the subjects, via equal parts speculation and historical confirmation, and explain it all through a unifying theory about why such a complicated work of art was created. It is an effort as ambitious and mystifying as the painting itself.

Lavish is exactly the right word to describe the quality of the publication. Unless you had the good fortune, prior to 2002, to visit Strathtyrum House, that grand estate owned by the Cheape family overlooking the St Andrews links, you would never have experienced the rich color and personality present in this immense 7-foot wide landscape. Fortunately, the painting now rotates between the British Golf Museum, Scottish National Galleries in Edinburgh and various traveling exhibitions over the past several years.

Through crisp photography and creative thematic groupings, Alastair Loudon has given us as golfers a glorious treatment to savor, with detailed information about all of the characters on display; who they were, what they meant, and why they might matter to us today.

As a piece of visual art, the book is a smash success. As a reference guide for coming generations seeking to untangle the meaning of Lees’ work, Loudon’s unflagging research efforts have contributed something new and enduring to the history of the game. For the first two achievements alone the book is a worthy contribution to the library of golf. As a persuasive argument of historical narrative, however, Gentry Links proves highly stimulating but ultimately unsatisfying.

The unifying notion of Thomas Carlyle’s “Great Man Theory” is a tempting talisman, but is not fleshed out enough to prove conclusive for this reader. Though several mentions are made to Sir Francis Grant, and several of his portraits are included, no reference is made, visually or otherwise to his similar (and earlier) work in the genre, First Meeting of the North Berwick Golf Club in 1835. This seminal artwork is on display at The Links Club in Manhattan, where interest was revived in recent years through its rediscovery by the late David Malcolm. How the Grant painting from North Berwick could have influenced the Lees work in St Andrews is unclear because it remains unaddressed.

Loudon’s detailed book offers a very good word in a continuing conversation. How dull it would be were it the final word! Thanks to Loudon’s efforts I know I’ll enjoy many conversations in the years to come about what this famous, and overlooked, piece of golfing art might really mean. For that this reader is thankful.