Courtesy Tennessee Golf Hall of Fame

Celebrating black golfers – Theodore “Teddy” Rhodes

By Jim Davis

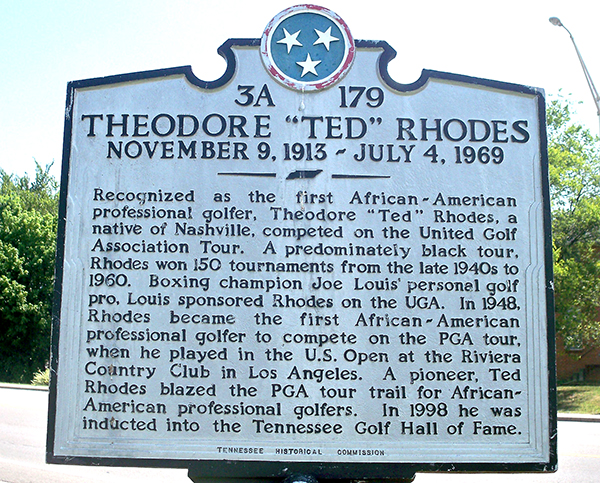

He had a prodigious talent for golf, sometimes compared with Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus. But only a few lucky souls got to see Theodore Rhodes play golf. He was was born in Nashville, Tenn., in 1913, a year after Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, and Sam Snead. But those men had early 20th century American cultural prejudices on their side – they were born caucasian while Rhodes was an African-American.

Rhodes would join Lee Elder and Charlie Sifford as icons of the game to those who recognize them for their roles in the evolution of professional golf and of helping others learn to overcome many decades of racial disparity.

In his book, Just Let Me Play, Sifford wrote that Rhodes was about 20 years ahead of his time, too much of a gentleman to fight tooth and nail against a system rigged to deny him opportunity.

Rhodes attended Nashville’s public schools and learned to golf while working as a caddie at Nashville’s Belle Meade and Richland Country Clubs. He earned a nickname of “Rags,” because of his often tattered clothing. He kept playing, digging his game out of the red clay fields on which he had access. His daughter, Peggy White, said her father “lived to play golf… It was his passion.”

In the late 1930s, Rhodes joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) then enlisted in the United States Navy in World War II. Life after his discharge found him in a culture virtually unchanged with regard to racial prejudice. While unwelcome to play in most of the prestigious tournaments, the 32-year-old Rhodes received an invitation from George May to play in the 1946 Tam O’Shanter tournament in Chicago. It would be his first exposure to large crowds, many of them at best curious about the black player, many downright hostile. Rhodes finished 43rd and took home a most welcome check for $150.

Paul Runyan was one who thought Rhodes a man of exceptional talent, but one facing so many obstacles. “…during those days, the black kids were playing under a cloud. They were not as welcome as they should have been and as a result they didn’t get a fair shot.”

On the United Golfers Association tour, however, Rhodes excelled. Like the Negro National (and American) League, the UGA offered black athletes an opportunity to showcase their skills. Rhodes would win the UGA championship in 1949, 50, 51, and 57. He won elsewhere, too. In a tournament at the Rackham Golf Club in Detroit, he met boxer Joe Louis, a self-described “golf junkie,” who took a liking to Rhodes and hired him to become his personal instructor, valet and playing partner. In effect, writes author Pete McDaniel (Uneven Lies, 2000), Louis became Rhodes’ sponsor.

In the late 1940s Louis sent Rhodes to southern California where he was mentored by Ray Mangrum, brother of 1946 U.S. Open winner Lloyd Mangrum. He began to refine his game on the public courses of Los Angeles County. In 1948, Rhodes played in the U.S. Open at the Riviera Country Club in Los Angeles, Calif., and became recognized as the first African-American professional golfer. He drew some considerable galleries. His first round 70 was only one off the pace set by Ben Hogan and Lew Worsham. That got more than few people nervous. After all, the top 24 finishers in the U.S. Open received invitations to play in the Masters. Hands were wringing. As it turned out, Rhodes fell back – we can only imagine what pressures he must have felt – to finish at 302, tied for 51st and 26 shots behind Hogan who won the first of his four (official) U.S. Opens.

Also that year, Rhodes and fellow African-American golfer Bill Spiller brought suit against the Professional Golfers’ Association of America (PGA) seeking removal of the association’s “Caucasian only clause.” Although it settled out-of-court in favor of the two golfers, the PGA countered by changing its tournaments to “invitationals” and promptly invited only whites to participate.

Rhodes returned to the UGA where he found his greatest successes, but also did well in the two Tam O’Shanter events in 1949. Rhodes made the best of every opportunity that came his way. He rarely complained, it is said, and kept up his easygoing ways.

It is estimated he won about 150 UGA-sanctioned tournaments during his career. He eventually played in 69 events on the PGA Tour, and earned a paycheck a least 24 times, nine of them for top-20 finishes. In 1952 he, Charlie Sifford and Bill Spiller became the first group of blacks to compete in a PGA of America tournament, the Phoenix Open.

Rhodes began to ease off competitive golf somewhat later in the 1950s as a kidney ailment began to take its toll, though he still managed to beat Sifford by three strokes for the Negro National Open title in 1957, and take home a handful of other titles. In November 1961, the PGA finally rescinded its caucasian-only clause, but Rhodes had by then officially retired. He also wanted to spend more time with daughters Peggy and Deborah.

He returned to Nashville in the 1960s and mentored several black PGA players including Lee Elder and Sifford. Althea Gibson, the noted tennis player, turned to Rhodes for lessons when she made the transition from tennis to golf.

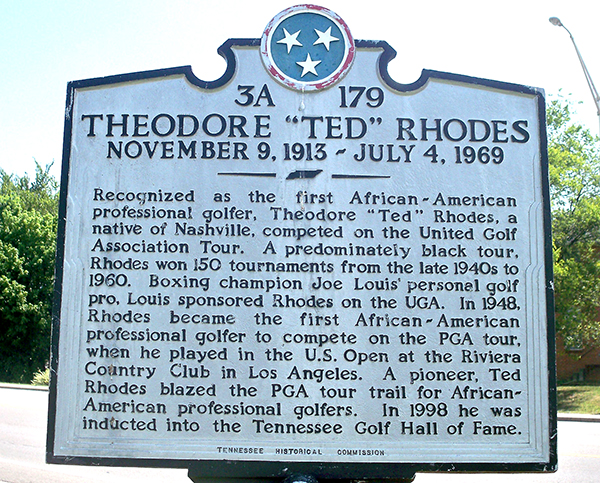

He died at the age of 55 in 1969. A month after his death, the Cumberland Golf Course in Nashville was renamed in his honor and is now named Ted Rhodes Golf Course. In 1998, Rhodes was inducted into the Tennessee Golf Hall of Fame. In 2009, the PGA of America granted posthumous membership to Rhodes, Spiller, and John Shippen, the early professional at Shinnecock Hills. During his first Masters win speech, Tiger Woods credited Rhodes as one of the pioneers who paved the way for all black golfers who followed him. In 2010, Rhodes was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame.

In 1993, the Ted Rhodes Foundation was created to educate others about his contributions to the game of golf and to host golf tournaments for youth and adults, as well as golf clinics. The foundation is run by Rhodes’s granddaughter, Tiffany White. The foundation supports the golf teams of historically black colleges and universities such as Fisk University in Nashville, and provides scholarships to golf team members. The foundation supports urban junior golf programs, such as First Tee of Tennessee and First Tee of Lake County.

The foundation’s work is a fitting tribute for a soft-spoken man who quietly went about his business, not letting prevailing racial attitudes spoil his enjoyment of the game he loved.