By George Petro

Intrigued by golf’s rich history? Then you won’t regret getting hooked on collecting its medals and trophies. Many are objects of compelling design, beauty and value. Most are also tangible representations of events and human struggles with which a collector, item in hand, can deeply identify and explore. So, charge in as a beginning explorer and emerge an expert, the curator of your personalized collection.

Organizing and displaying your collection is a labor of love in addition to nurturing an investment. Your theme might be to choose items that simply strike your eye representing a broad mix; or assemble appealing variations within a specific category; or focus on examples that tell the story of an era, persons, places or events.

Immediately following are sections on:

Medal and trophy design categories

Details and Definitions

Where and How Much

History of the Earliest Golf Awards

Medal and trophy design categories

Engraved prizes with utilitarian function such as silver putters, ink wells, flasks, mugs, watches, vesta cases (match safes used pre-WWI before “safety matches), cigarette and compact cases, etc.

The majority of widely available medals and trophies originate from the U.K. and the U.S., but there are many happy surprises. In Britain, golf awards since the late 1700s (aside from prize feather balls) have been dominated by medals. Until around 1900 most early American awards are a more balanced mix of medals and trophies, but trend toward trophies post 1900.

Design elements on these early Scottish medals include “Crossed Clubs,” mottos such as “Far and Sure” and depictions of the thistle flower (the national emblem of Scotland since the 13th century). Above, from left: Burgess Society 1831, 1868, and 1894; Thistle GC 1822. Bottom, from left: Bruntsfield Society 1828; Independent Caledonian Golf Club 1810 society medal and 1821 winners medal (that club’s existence is unrecognized save for its surviving medals); and Musselburgh GC 1832. A history of the ancient societies and their awards can be found below under History of the Earliest Golf Awards.

There is a clear distinction between medals and trophies that are “permanently” held by a society/golf club and engraved with the many names of prior winners, and those directly awarded, or given, to those winners. Not unexpectedly, the former are relatively scarce. Early tradition was sometimes to retire the society medal or trophy to the competitor who won an event three times in succession (as was the original British Open trophy belt won and retired by Young Tom Morris and replaced with the Claret Jug). The heavy gold medal on the left (above) dates from the founding of the North Berwick Club in 1832 with the smaller hanging portion providing space for additional names through 1849. It was won outright by Sir David Baird (a featured player of the famous painting by Charles Lees, The Golfers) with victories in 1847-49 and subsequently passed down through his family and eventually publicly sold. The permanent medals and trophies of bygone societies occasionally become available to collectors and museums.

Early American trophies from 1894 to 1900 of varied composition ranging from silver, pewter, brass, copper and enamel overlaid metals to wood, crystal and ceramics. Some even with antler handles.

Examples of medals from around the globe include Royal Montreal, Belgium, Chile, Uruguay, India, Sudan, France (in rectangular “plaquette” form) and South Africa.

Trophies from Uganda, left, Iraq, and Japan.

Medals from U.S. inter-state and intra-state competitions (often with official state “seals”) and from various city and innumerable individual club events.

Medals with British heraldry that depict inter-county and inter-club associations can be pleasingly displayed and grouped to define golf competition in a particular region or era.

These larger trophies include one 23-inches tall, left, won by Frances Ouimet, displayed with a photo of him standing proudly next to it on his fireplace mantle. The green glass trophy, center, has an engraved silver overlay. The Amateur Championship of Southern India trophy has names from 1906 to 1945 engraved on its silver and wooden “plinth” that include numerous military officers during the time of rule by the British Crown.

Miniature trophies/awards given to players are sometimes small replicas of permanent trophies. Medals offer an advantage over larger trophies with the convenience of easy transport and just right for small apartment living, though few objects offer the visual impact of large and striking trophies.

British “Ladies” and U.S. “Womens” trophies and medals are some of my favorites.

Many medals have a ribbon and most sport at least a “suspension loop” and often a “suspension ring” that allow attachment to a ribbon. Typically, there is a “top bar” and some sort of pin mechanism called the “brooch” for wearing.

Colorful Red Cross and War relief medals are reminders of golfs’ long history of philanthropy. Design themes, apart from featuring a golfer in period dress and swing form, might otherwise include various animals, landscapes, architectural elements, ships or represent educational institutions. The world is your oyster.

Crows, owls, elephants, lions, bears, bulls, fox, and goats are shown above.

Buildings are the primary design theme.

Shown above are golf medals from various educational institutions, including Michigan high schools, a Catholic summer school, NCAA golf, Yale and Oxford universities.

Awards tell stories, such as the tale of Mrs. Naylor, the Honorable Secretary of the Huddersfield Ladies Golf Club, whose medals show that in 1903 she had a handicap of 14 in the 2nd Class division, advanced to 1st Class competition by 1907, and won the most prestigious medals of her club by 1912.

PROFESSIONAL TOURNAMENT MEDALS AND TROPHIES

It is not uncommon to find reasonably priced medals from well known amateur or professional tournaments; not infrequently, even those related to such impressive events as The Ryder Cup or from the four professional “Majors.”

Closely related fields are the collecting of OFFICIALS MEDALS/BADGES supplied to tournament organizers and PLAYERS BADGES (and money clips) to all contestants in the field, serving as credentials for entry onto the course and facilities during many tournaments.

SOME DETAILS AND DEFINITIONS

MEDALS are almost always struck (like coins) with the chosen metal compressed between steel dies. Larger examples called MEDALLIONS (usually over 4 inches) are frequently cast by pouring molten metal into molds because of difficulties in striking larger pieces. Medals are typically awarded for achievement while medallions often commemorate a person or event or may be produced for artistic expression. Medallions may be worn on long ribbons or chains around the neck though often are displayed as “table medals.” (Military medals/decorations were known to be awarded since the 4th century BC).

The obverse, or front, of a medal has the dominant design. The reverse side is usually reserved for engravings but may have intrinsic inscriptions, peripheral laurel wreaths or secondary designs.

TROPHIES, as we have seen, can have numerous forms. Items such as heavy silver candlesticks or other solid designs are typically cast by pouring molten metal into molds. Thinner objects might be made by stamping a sheet of silver between dies. Filigree objects are created from soldering twisted silver wire into decorative patterns and forms. The majority of sterling trophies are hollowware made by one of following three methods.

Raising – A silversmith painstakingly hand hammers a round silver disc at its center and concentrically outward achieving a shallow saucer shape. This initial hammering is on what will be the inside surface. In the second stage this is reversed with the concave side held against a steel or wooden “stake” with continued hammering on the outside surface to raise the sides to the desired height. Hammering compresses the silver into a harder state that requires repeated red-hot heating and sudden quenching in water to partially re-soften the silver and allow further hammering. The finished product is strengthened by this repeated process called annealing. Extremely fine hammering is followed by polishing, leaving a smooth bright shine. This method may take days to complete.

Seaming – A sheet of silver is wrapped into a cylindrical shape and soldered at the seam. A silver disc is soldered to the open bottom and hammering can complete the shape. Often a handle is attached along the soldered seam.

Spinning – This process begins with the creation of a hard form, called a chuck, which has the shape of the final piece. A thin silver disc is then firmly attached to its bottom and both are spun together on a lath-like device. The thin silver is firmly pushed with a tool onto the surface of the chuck thus wrapping tightly around it. The top edge is sometimes turned back on itself to add rigidity. Extra silver might be soldered to the top edge just as feet or handles could be with any of the three design methods. The basic shape can be achieved in minutes.

ENGRAVING – The removal of material to create scenes and inscriptions (words/letters).

REPOUSSE – The technique of hand punching and hammering (or sometimes using embossing dies) from the back/inside of a metal piece to create a relief (raised) design on the front/outer surface.

CHASING – This involves indenting the front surface, using fine tracing tools and hammer, which gives the non-indented portions the appearance of being raised. Inscriptions using this technique often have a flowing or melted look that can be highly artistic. The combined use of repousse and chasing may be referred to as embossing in which scenes raised from behind can then be beautifully enhanced by fine chasing and/or engraving from the front. A “hammered pattern” results from intentionally placing broad hammer marks on the surface.

APPLIED DECORATION – Silver additions (often separately cast) are soldered onto the trophy or medal to create ornate designs or borders. Handles, spouts and feet are often examples of soldered additions.

SILVER PLATE – This has long been a cheaper substitute for sterling silver which is at least 92.5 percent pure silver. Old Sheffield plate, invented in 1743, in part to reduce silver taxes, consists of a thinner sheet of silver fused to a thicker one of copper that together could be shaped into high quality hollowware with the copper on the inside and later double plated with silver both inside and out. Elkington’s patent for silver and gold electroplating began to replace it in the 1840s with modern silver plate having pure silver electrolytically applied to a base metal. Look for the initials EP, EPNS or EPGS. Many plated pieces remain very collectible.

GILDING – The application of a thin layer of gold to various materials. When applied to silver the result is called silver-gilt or vermeil. Silver atoms can diffuse into the gold and eventually fade or tarnish, so barrier layers of copper and nickel are used. Gilded trophies are uncommon.

ENAMELING – The use of powdered soda or potash with silica and colored metallic oxides, etc. and heat-fused onto metals such as silver and gold.

The heavy 1898 Allegheny GC trophy (Pennsylvania) on the left sports an engraved scene of a caddie and two golfers on a teeing ground, but the dominant features are the applied ornate flowered bands and three handles. The inside of this trophy is smooth. The other is from the 1904 Olympics. Its dominant feature is the thistle flower, which extends outward in high relief as a result of the repousse technique of hammering on the inside of the trophy to drive material out. The detail is enhanced by fine chasing (hammering of the outside surface) of the flower and also creates an artistic inscription below without using engraving techniques. Further applied elements are soldered to the handles and upper rim.

Evolution of trophies post WWII moved further away from traditional sterling silver cups and toward figural forms often using base metals. Similarly, early medals of gold, silver or bronze also shifted toward the use of base metals with a gold color and often with less inspired designs as well. Thus, many collectors focus on pre-1930s examples.

PROVENANCE – This refers specifically to the known record of prior ownership, a key factor in judging an item’s authenticity. Fortunately, most medals and trophies adequately explain themselves by having appropriate physical form, engraving and quality. The more examples you see (at trade shows, in museums, in books or featured in on-line golf auctions), the more competent you become at discerning authenticity, quality and pricing.

It is possible for the unscrupulous to first acquire a genuine desirable medal and then produce a copy by creating a mold to cast a fake (producing more than one would be doubly suicidal). The giveaway would be the unsharp graininess of the crisply struck original and likely have off-tone patina. Engraving proper medals with incorrect information is possible but is not worth the effort unless the change is to a more significant event or from a more famous winner, and in those cases the risk of eventual discovery is high. Period silver items have been engraved as if being trophies, but the penalties are high (tantamount to money counterfeiting). This and occasional innocent misidentifications are rare, largely negated by solid provenance, common sense and experience.

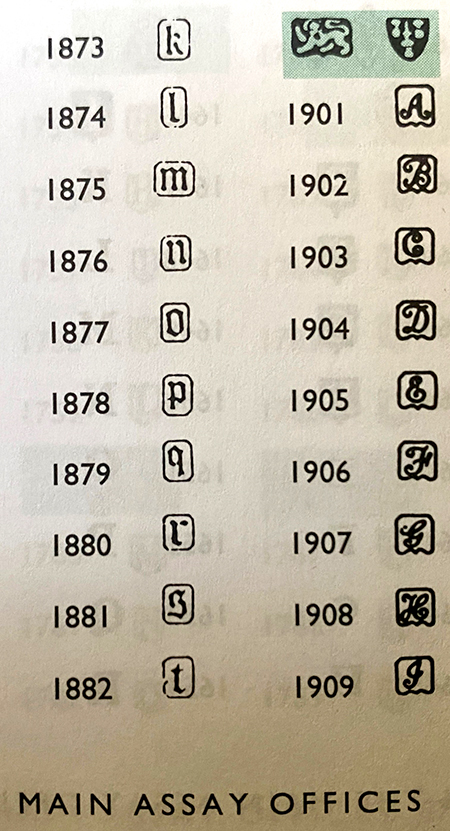

HALLMARKS and MAKERS MARKS – Any collector should have at the ready a magnifying glass and easy access to published listings of such marks. They are highly regulated by law, tiny indentations hammered into any items of gold or sterling silver made in Britain (usually) at the time of their creation that identify the place and date of its assay verifying its precious metal content before any sale. It is also a way to date an object not otherwise evident. While not infallible, deciphering any mark is a simple, informative and reassuring exercise. A number of other countries have long used hallmarks as well but tend to be more loosely organized. There was no such uniform regulation of silver purity or system of date and location marking in the U.S. New York and Boston had societies of silversmiths so medals and trophies from especially those areas since the 1890s may be marked with the maker’s name and city, and dates only very infrequently. Modern American silver should be marked with the maker’s name and numbers regarding purity. STERLING refers to .925 purity. Often vessels are marked with volumes.

where and how much?

The exuberance associated with the unexpected flea market or antique shop find isn’t dead, but more often we go where the action is concentrated by middlemen who save us miles of legwork via eBay, on-line specialty golf auctions (their website links are listed on our Resources Page) and various dealers. The anticipation of the hunt rises as you press the “Enter Current Auction” button or when the doors open at a GHS Trade Show. After-auction prices with extensive descriptions are available for review and there are at least two active auctions running in any given month, each with from 250–1,000 lots, including numerous golf medals and trophies. Auction catalogs from major general auction houses since the 1980s are invaluable references. After the hunt, the process can continue with more research, organizing, displaying and sharing.

PRICES range from $30 to $300 for the vast majority of interesting medals and $100 to $1,000 for most trophies. Not infrequently the asking price of many a nice sterling trophy or gold medal is only marginally higher than its melt value and can be a rewarding buy if it fits your collecting plan. Rare or unique pieces, not presently on the radar of other collectors, need not be expensive. We may still be on the ground floor in appreciation of golf’s medals and trophies, compared for instance to the long mature and massive field of military medal/decorations, given that there are 30 million people playing some form of golf in the U.S. alone.

There are obvious premiums for gold medals over those of silver or bronze, and generally for larger medals/trophies over smaller ones. But visual appeal trumps composition and historic significance or a compelling story and items from an important golfing legend tend to dominate all else.

At the highest end, a Masters’ 3D Clubhouse trophy, one of four belatedly awarded to Arnold Palmer, sold for $440,000 and a gold medal from the 1904 Olympic golf competition brought $273,000 at auction. The earliest styles of Open Championship and U.S. Open medals command well over $100,000. The American PGA Championship winners’ medals are not only gold and of high artistry, they all feature a genuine diamond. Considering two PGA winners medals – one might be priced at $20,000 and the other $85,000 if it was won by the great Walter Hagen. Awards from the likes of Nicklaus, Woods or other millionaire pros are currently unattainable at any worldly price, however, some from the stars of earlier generations like Vardon, Hagen, Sarazen, Snead and even Jones have become available. Runner-up awards from well-known events might roughly average about 20 percent of the winners’ prices. Pre-1850 medals have shown a wide range from $2,000 to $50,000 (the 1832 North Berwick Society Gold Medal pictured above).

But an important and rewarding collection need not break the bank. Most historic pieces (find your niche) have markedly lower prices that vary by date, event and story. The knowledgeable collector who suspects that a “routine piece” has a special association or recognizes an engraved name, can acquire a piece quite cheaply before the value multiplies many-fold after its significance is exposed. Those are the collectors who seem to repeatedly score the lucky finds. (At shows, I bring along a book that lists all participants in USGA events since 1895, a similar book of records of British/World event winners and a copy of H.B. Martin’s 1936 book, Fifty Years of American Golf.) Numerous medals in my collection cost less than $200. Just this month (July 2020), I purchased for $100 on eBay, a 1908 sterling golf trophy from Arlington, Ohio bearing the name Mrs. S.P Bush. Yup, the paternal grandmother and great-grandmother of former U.S. presidents 41 and 43. I now know the entire family tree and their many connections to golf history.

HISTORY OF THE EARLIEST GOLF AWARDS

The earliest societies conducting organized play appeared in the 1700s, long after golf was more randomly played on many ancient courses known since the 1500s. Their specific dates of formation as a golfing society/club are open to some debate but the general consensus is: The Burgess Society-1735, Honourable Company-1744, St Andrews-1754, Bruntsfield-1761, Blackheath (London)-1766, and Musselburgh-1774, etc.

The first documented “tournament” was played on Leith Links in 1744 by the Gentlemen Golfers of Edinburgh (later known as the Honourable Company). A Silver Club was presented by the Towne to the Company for annual competition, the winner automatically becoming the Captain of the Golf for the ensuing year. Upon completion of his term a silver or gold ball with his name was affixed to the shaft of the silver club. He was able to take temporary possession of the club in lieu of satisfactory deposit and safeguards. (There had earlier been the Edinburgh Arrow and St Andrew University Silver Arrow competitions for archers). With a significant cross-membership, St. Andrews followed with a similar Silver Club Challenge in 1754 as did Blackheath in 1766 (and Glasgow in 1787). The Musselburgh GC instead began play for a large silver cup in 1774, played for annually and available for possession by the victor who was obliged to append a “medal” to it when he restored it to the Company. Winning at Musselburgh included automatic elevation to the office of “Praeses,” or presiding officer of the Company.

None of the early winners received medals or cups until…

The first ever golf medal of any type was awarded by St Andrews to Colin Beveridge on Oct. 2, 1771, for a secondary competition held the day before the Silver Club Challenge in hopes of encouraging travel to their fall meeting. Its whereabouts is unknown.

The first “awarded” cup was the result of that same St Andrews event having replaced the prize with a silver cup for its second year in 1772 and again in 1773 and 1774, but was discontinued thereafter (per Challenges and Champions, Behrend & Lewis 1998). I don’t believe any of the three exist?

In 1774, the Honourable Company also instituted a yearly Silver Cup competition, the first cup purchased by the Society and thereafter by the winner for presentation to the following year’s winner (apparently this burden led to the end of the event after 1801). Three of these cups are known to exist, dated 1774, 1776 and 1790.

To my knowledge, the next existing trophy “presented” by a golfing society to a participant is particularly remarkable because it is not silver, but rather a large porcelain punchbowl (Spode Co.) which reads, “Bow Of Fife Golfing Club – Prize Medal for 1814 –Won by John Pitcairn Esq. of Kenneard.” It is the unique record of a lost society playing on an extinct Scottish course, known only because of this historic prize pictured below.

In 1790, the Honorable Company became the first society to begin competition for a “Society Gold Medal” engraved with names of its winners. As with the silver club competition, it was played for, but not awarded to the winner. This second of the two earliest medals has also been lost.

The oldest golf medal still in existence is from Blackheath, and specifically from a more secretive club within the parent society, called the Knuckle Club, which provided itself a blue, green and white enameled gold medal with a clamshell design for competition in 1792. Opening its hinged cover reveals numerous gold plates, each engraved with winners’ names and dates. It is a spectacular visual and historic piece (photos available on-line).

In 1806, St Andrews instituted its Society Gold Medal competition, then held two days after the Silver Club Challenge. That medal is engraved “Prize to the Best Golfer of the ST ANDREWS CLUB.” This is the era when other societies were selecting/electing their captains, starting to move away from assumption of the office by the earlier true test of skill in playing for the Silver Club, since clearly, the most proficient golfer might not make the best Captain (for running meetings, organizing the golf and arbitrating disputes) nor want the responsibility.

The Burgess Society presented a now missing gold medal to an individual in 1807. This oldest society finally started a typical gold medal competition in 1816 as did the Bruntsfield Society in 1819.

Note: It was not until the late 1820s that these prominent societies actually presented an individual medal for winning their gold medal competitions. In the medals shown earlier, you will see an example of the scalloped margin, silver medal engraved “Edinburgh Burgess Golfing Society, FAR AND SURE, Presented to Walter Lothian Esq. HOLDER OF THE GOLD MEDAL, 16th April 1831.” It is an exact replica of the Society-held medal but silver rather than gold. Walter also won the Bruntsfield competition in 1826, both societies playing on the same course. The pictured round medal is for an individual winner in 1828 (probably the first year the club directly awarded medals) inscribed “BRUNTSFIELD LINKS GOLFING SOCIETY INSTITUTED A.D. 1761 GAINED BY Mr. Samuel Aitken 27 SEPTEMBER 1828.” He won it a record eight times between 1825 and 1842, and the Burgess Gold Medal twice as well.

Also pictured among the medals is the Independent Caledonian Golf Club (instituted 1810) “society” medal (non-gold) with winners’ names on the reverse. Adjacent is the smaller matching winners medal from 1821, possibly the oldest “existing” individual medal. Both are from a less prestigious golfing society which is unknown to written records save for these medals. The famous Thistle Club (at Leith Links), was established in 1815 with an awarded individual medal to in 1822.

(Pictured items in this monograph are from the collection of the author.)