Dick McDonough, who passed away in 2021, was a passionate golf collector who loved early depictions of art and the history of golf art. He was an invaluable contributor to the Golf Heritage Society journals.

By Dick McDonough

The purpose of this article is to provide descriptive information, but more importantly visual evidence, of the popular stick and ball game akin to golf, known as colf, played in town streets, open areas and on fields in the Low Country (Holland) from the late 1300s until it died out in the 1700s.

Over the years there has been considerable confusion of terminology and inaccuracy about the various forms of recreational“golf” that the Dutch played over several centuries. A review of turn-of-the-late-19th century Scottish and British golf literature failed to provide detailed descriptions or distinctions between the different types of “golf” being played at different times in Holland. Horace Hutchinson in the 1890 edition of The Badminton Library-Golf took note of the Dutch game but based his writings largely on depictions of the game taken from visual images on tiles or pottery, noting “…the Dutch played a more golf like …kind of golf…” and based largely on those sketchy source materials and the evolution of the golf ball made the astounding and heretical statement, “This looks as if golf had its native seat in Holland.” Hutchinson also admitted he did not have the time to properly research the subject.

Andrew Lang, the leading golf historian of the day, took the opposite position observing “There is no specific resemblance whatsoever between golf and the Dutch game called kolf.”

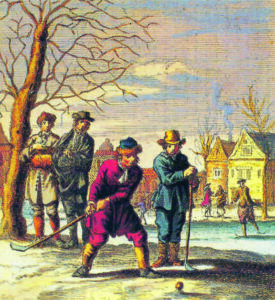

Golf articles written during the early 20th century began to takenote of the hundreds of Dutch and Flemish paintings of ice-skating scenes which invariably depicted a form of golf being played on ice. They described striking similarities between golf players in Scotland and their counterparts in Holland. Notable examples included two from Golf Illustrated – “Two Old Dutch Golfers”(Feb. 8, 1901), and “Two Old Dutch Engravings” (March 22, 1901);and “Concerning Golf in Holland” and an article titled, “A Primitive Golfing Scene,” both from Harper’s Weekly (April 15, 1899). That article reproduced an Aert van der Neer painting, shown below, and noted, perhaps for the first time, the painting made it clear that the Dutch were playing a form of golf on both land and ice.

Harry B. Wood, commonly regarded as the earliest preeminent collector of golf antiquities, published, Golf Curios and ‘The Like’ in 1910. His book contains nine plates of various Dutch-related golf artifacts, including tiles, portraits, and ice scenes, with emphasis on and early images of Kolven, the short game played on an enclosed court. Plate XI, shown below (and a later, colored version, at the top of this article), captures the image of a colfer on land in mid-swing playing from a tee. At the time, publication of this picture left little doubt that the Dutch were playing a form of golf on land as well as ice.

By 1920 the interest and prominence of Dutch golf art had exploded. That year Bernard Darwin published A Golfer’s Gallery by Old Masters. It was a portfolio of classic golf prints which he introduced saying, “…golf has produced a gallery of pictures incomparably better than those of any other game.” The predominance of Dutch art was apparent. His 19-page introduction contained 12 black and white prints by various Dutch artists, including the picture referred to above as Plate XI on the cover page. Similarly of the18 color prints which he regard- ed as ageless, respectable, and charming by old masters, 11 were painted by Dutch or Flemish artists. The portfolio was designed with instructions as to how each color print could be easily removed, framed, and hung. Based on the overwhelming content of Dutch art it was clear that public acceptance had arrived.

Nevertheless, despite the newfound popularity of Dutch “golf” art and publication of hundreds of books on the game no scholar had undertaken comprehensive and thorough research to uncover the true facts. It was a challenge taken up by Steven J.H. van Hengel, following in the footsteps of J.A. Brongers, who passed away in 1954. Van Hengel’s research was extensive and time consuming: centuries old city ordinances, guild records, tiles, artistic products, national and city office records, museums, libraries, public and private collections, and volumes of literature. In 1973 he shared his preliminary findings with The Golf Collectors Society through a series of articles in Bulletins 11, 12, and 13, titled, “Early Golf: History and Development.” He published the book, Early Golf, in July 1982, which remains far and away the most authoritative book on the subject.

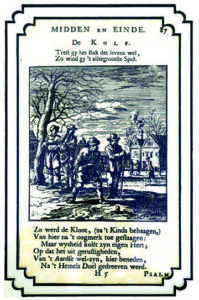

Beginning with the 14th century, van Hengel traces the development of the game century by century noting that at the beginning of the 1700s popularity of the game of Colf was waning. He points out that the term “Het Kloven” had taken on so many different meanings regarding golf-like games that it had a life of its own. In order to achieve greater precision and consistency he chose to define the Dutch games as follows:

- COLF: the old long game played in the Low Countries from about 1300-1700.

- KOLF: the history of the short game which developed out of the long game from 1700 onwards.

- GOLF: the history of the game that developed in Scotland around 1450 and continues worldwide today.

While it is helpful to simplify the terminology, the definition he chose for Colf is so broad and encompasses so many different games that important distinctions are lost. Van Hengel’s research makes it clear that from 1300 until late in the 1600s the popular Dutch game was Colf, the long hitting game played initially on streets, and when banned in various towns, moved to the town ramparts or fields. During the very severe winters of the 1600s the Dutch moved their game to the ice.

Based on clues from Dutch art it appears that some players continued to play the long game on land, some either on ice or a combination of ice and land, while others chose to play a sort of game often targeting a pole in the ice. Given the extreme distances a ball could travel on ice this adaptation is not the least surprising. Some Dutch art from the early 1600s captures both forms of Colf but given the massive crowds and varied activity depicted in the ice scenes the short game seems to have been more prevalent. The short game was and still is frequently referred to as Kolf whenever the old Dutch art – paintings, tiles, etc. – is referenced.

For purposes of this article let us assume, despite differing nomenclature, that the term “Colf” refers to a form of golf that was played on land and involved a club, a ball, and a full swing in order to play to a distant target.

Most Dutch art of 16th-18th century is considered genre painting, meaning scenes of everyday life with ordinary folk depicted in their homes, at work or recreation. The painters immortalized towns and landscapes capturing life in intimate variety: indoors, in taverns, neighborhoods, or in the street. Much of the Dutch middle class had achieved a level of prosperity that enabled them to acquire paintings which in earlier times would have been considered luxury goods. The Dutch artists realized there was demand for their work with a large market consisting of middle-class customers. Oil paintings of everyday scenes intended to be hung in the home were common and relatively inexpensive. The artists often used this medium to convey subtle or humorous commentary on family, social, or moral issues. This form of art represented a breakaway from the more traditional landscapes, portraits, religious subjects, battle, or historic scenes common throughout much of the artworld. Because of its realism this art has captured and preserved an accurate record of what life was like in Holland 400 years ago.

Delving into the wealth of that resource, I believe we can distinguish four distinct categories of art that shed light on the various forms of “golf” that were being played in Holland during 1300-1700 – Portraits, Tiles, Ice Scenes, and Images. These are discussed in the sections below along with sample images.

Because my focus is on Colf, the long game played on land, my emphasis is on the art that portrays, confirms, and sheds additional light on that game. For a detailed description of the game, its implements, playing grounds, and restrictions imposed by local authorities I refer the reader to van Hengel’s Early Golf. In addition to the descriptive text, he provides hundreds of images, including five pages of Dutch tiles of the period and two pages showing heads of Colf clubs dating back to 1600.

COLF – PORTRAITS

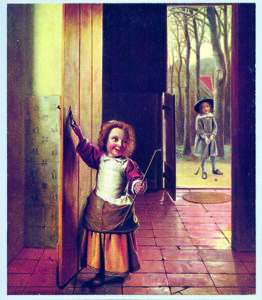

Dutch art during the 17th century was predominantly genre paintings. There are a considerable number of portraits of young children holding Kolf clubs and were most likely commissioned by wealthy families. These portraits have aroused considerable discussion and debate about their meaning in terms of the nature of the game being played in that period. Some early golf historians concluded that Colf was achild’s game rather than a long game played by adults. Frankly, the portraits shed little light on the game of Colf other than to capture images of the clubs and balls in use at the time. However, given the very small size of some Kolf clubheads recovered in recent years it is clear they must have been used by youngsters.

c. 1624. One boy addresses a large white ball (wooden?), his eyes focused on a target. The two boys are clearly engaged in a game of Colf on land.

TILES

We commonly refer to tiles depicting early forms of golf as Delft tiles but, in fact, tiles were first produced in Holland around 1570 with potteries located in five towns. They spread to six more towns in the early seventeenth century and continued their growth throughout the century. The definitive reference is Dutch Tiles by Dingeman Korf (Universe Books Inc., 1964). The book traces the origins of tiles, the process of making them, their popularity and use, and the decline of the industry in the late eighteenth century. (Also refer to “Collecting Delft Colf Tiles” in the Autumn 2018 issue of The Golf.)

The earliest Dutch tiles, pre-1650, frequently portray a player holding, and sometimes swinging, a lengthy club characteristic to what would be used to strike a ball some distance. (Two samples from the author’s collection are shown above.) With few exceptions later tiles depict a single player using a much shorter club often aiming at a nearby target such as a stake or hoop. Tiles from the late eighteenth century onwards almost universally show two players each holding a short club engaged in a game with a visible target nearby. These later tiles are characteristic of the short game depicted on hundreds of paintings of ice scenes. One might conclude that the earlier tiles represent Colf players engaged in or preparing to play the long game on land.

ICE SCENES

During the seventeenth century, Holland frequently experienced severely cold winters known as “The Little Ice Age” (1550-1650). The harsh winters caused the rivers, canals, and shipping lanes to freeze solid, impacting the people as well as the Dutch economy, which was heavily reliant on trading. While the brutal winters caused hardship, they also created an opportunity for fun on the ice – skating, sledding, and such games as Kolf. Artists captured the scenes by painting literally hundreds of ice scene paintings. The list of accomplished artists who painted these scenes is practically endless. A few are listed below the images. Their works are displayed today in prominent art museums throughout the world. Such paintings by accomplished artists that reach modern auctions frequently fetch six or seven figures.

An examination and analysis of this artwork is beyond the scope of this article. Dozens of articles and books contain a variety of the outstanding paintings. Most of the “golf” depicted in the paintings is of the short game variety, although, occasionally, a Colfer can be seen taking a full swing in a very crowded area with apparent disregard of the consequences. Hendrick Avercamp (1585-1634) painted dozens of ice scenes and is regarded as the most accomplished artist of this genre. His paintings at right are typical of his style and illustrative of Colf players enjoying their sport on the crowded icy canals.

*Prominent Dutch and Flemish artists who painted ice scenes involving Kolf or Colf:

Esaias van de Velde (1587-1630)

Hendrick Avercamp (1585-1634)

Jan Steen (1626-1679)

Aert van der Neer (1603-1677)

Adrian van de Velde (1636-1672)

Isack van Ostade (1621-1649)

David Teniers-The Younger (1610-1690)

Paul Brill (1554-1626)

Jan van Goyen (1596-1654)

Interested readers would be well advised to find a copy of the three-book series Games for Kings and Commoners by Geert and Sara Nijs. The books explore in depth the early European games and are complemented with wonderful images. Information at: www.ancientgolf.dse.nl.

Contributions by the Nijs to The Bulletin:

December 2012 – book review, Games for Kings and Com- moners, Part I

December 2014, book review, Games for Kings and Com- moners, Part II

March 2015, article, Early Golf in America

September 2015, article, Artic Colf

March 2016, article, Collecting European Clubs & Balls

COLF IMAGES

As some golf historians have questioned the existence of Colf, the long game played on land, I have assembled some paintings or related images portraying the game being played on land or that capture scenes of a young male Colfer. These pictures are a small sampling of the dozens of period art that conclusively demonstrate that the land game of Colf was popular in the low country during the 1600s and earlier.

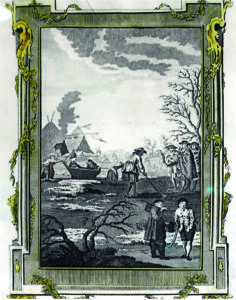

This oil painting captures the image of colfers clearly playing over land, though quite near a frozen canal.

and Universal System of Geography, published in 1782. The engraving portrays winter diversions of the Dutch. The colfer in the center appears to be wearing a kilt, while colfers in the forefront appear to symbolize more traditional Dutch attire and clubs. From the author’s collection.