1956, is a William Diddel gem, though reworked in 2002 by Pete Dye.

In this article, golf historian Curt Fredrixon explores the life and work of William H. Diddel, a founding member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, and one of the country’s most prolific golf course designers. After reading Curt’s article, you may come to agree that Diddel is one of the country’s top architects that you never heard of. Previously published in the Summer 2022 edition of The Golf.

By Curt Fredrixon

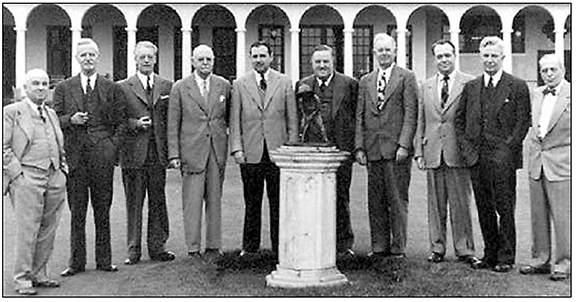

On Dec. 5, 1947, an iconic photo that many have seen was taken. It was on the occasion of the first annual meeting of the American Society of Golf Course Architects at Pinehurst, N.C. Pinehurst, of course, was the winter base of Donald Ross and, along with Ross, Stanley Thompson, Robert Trent Jones, and others in the picture, over there, second from the right, was William Diddel.

“Whom?,” you may ask. Well, Bill Diddel may have been the busiest Golden Age golf course designer of whom you have never heard. Wikipedia claims that he was responsible for close to 300 golf courses and lists 98. I have found contemporary reports from well before his design career ended that credited him with around 200 courses.

The late Paul Fullmer, who was the long-time executive secretary of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, said of Diddel, “He believed you could contour the land subtly to challenge golfers without creating large mounds, water hazards or 100 sand traps, and could do it within a reasonable budget.”

William Hickman Diddel was born in Indianapolis, Ind., on June 7, 1884. His father, Andrew Jackson Diddel, was born in 1844 in West Virginia. “A.J.” married Letitia Jane Hickman (born 1845 in Kentucky), the daughter of an Indianapolis clothing merchant.

Early in his adult life, Andrew was a railmaster, an administrative position in which he was responsible for the maintenance of a specified portion of his employer’s railroad track. Later, he worked in the life insurance business, operating his own agency. Since golf at the time was still largely a sport for the affluent, it must be assumed that business was good enough to give Will, as Diddel was known early in his life, access to the game.

Will attended the Industrial Training School (later the Manual Training High School (MTHS), now the Charles E. Emerich Manual Training High School) in Indianapolis. Reports suggest that Will was a joiner and that he had a tendency to be chosen as an officer of organizations that he joined. MTHS did not have a golf team, but students formed a golf club, of which Will Diddel was elected the captain. His matches were sometimes reported in a local newspaper. In May 1902, a “summer sketching club” was organized, of which Will was the treasurer. Its mission was to “take trips to the country and study nature.” An interest in sketching and nature could have been the embryo that grew into an interest in golf course design.

Despite a lack of size (later in life he stood 5-foot six inches and weighed 140 pounds), Diddel was a multi-sport threat. He was a member of the MTHS basketball team that won the Indianapolis League championship in 1902-03. At Wabash College he lettered in four sports (baseball, basketball, football, and track). The Wabash basketball team lost only one game, often playing against larger schools, during Diddel’s four years there and won what was considered to be the national championship one year. Will’s high school and college play earned him a place in the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame. While at Wabash, he created a golf course (called the “Phi Gamm” course, after his fraternity, Phi Gamma Delta) on vacant land south of the campus. He graduated from Wabash with a bachelor of arts degree in 1908.

In 1910, Will, as were his sister and older brother, was employed as a life insurance agent in his father’s agency. His eldest sister was the office cashier. Although he continued to be listed in business directories as a principal in this business, in February 1915 he was hired as the Athletic Director (the title varies with the source) at his alma mater and moved to Crawfordsville, Ind., where Wabash was located. Among his duties was traveling the state in search of athletic talent. He surprised Wabash when he resigned this position in December 1916 with a stated intent to go into business in Indianapolis.

In 1918, Will, his father and his brother, Glenn, in addition to being listed as principals in the A.J. Diddel & Sons life insurance agency, also were listed as principals in a dealership in Indianapolis representing the Franklin Motor Car Company. This existed until at least 1920 when the brothers were listed as “Diddel Bros. (Franklin Motor Car Co.)” and appeared to have been out of the insurance business. Franklin (ad above c. 1920) was known for its air-cooled engines. As a part of a Franklin promotion that led to a national newspaper ad campaign, Diddel set a world’s record by driving a Franklin 832.6 miles in 24 hours (22.5 hours of actual driving), a record later broken by another Franklin dealer from Iowa.

In 1913 Will Diddel married Julia Catherine Brubeck, who, like his mother, was the daughter of a local clothing merchant. The couple had two daughters, Jane (b.1916) and Judith Ann (b.1920). Julia died in an accident in the 1940s and Diddel married Helen Dickey, circa 1945.

Golf

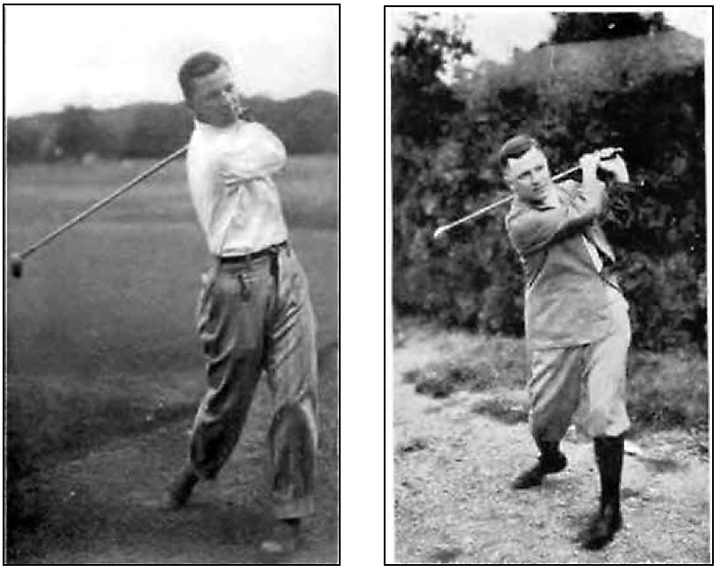

In 1900 Will Diddel was reported to have caddied for later Open Champion Sandy Herd for a course-opening exhibition. This experience engaged his interest in the game. The Indiana State Amateur Golf Championship had first been held in the same year, but when young Will showed up he almost made the Championship his personal property, winning it in 1905, 1906, and 1907. After a two-year “slump,” he returned to win it in 1910 and 1912 before, with marriage beckoning, stepping away from competitive golf for a few years. He returned to the Championship in 1918 and was the runner-up that year, but stayed away from the game after the war until his work as a golf course architect brought him back to playing as a pastime. For a while, his results were indifferent, but the old competitive fire was rekindled and, although he never won the Indiana Championship again, he was the low medalist in 1927, 1928 and 1930, against competition that had surely grown stronger since his best days, he was the runner-up. Business must have been a distraction. In multi-day club events, it was not uncommon for him to be allowed to play two rounds in one day so he could attend to business on another day of the event. He continued to play in the state championship in the 1930s and qualified for it in 1955, 50 years after his first win.

Diddel had mixed results when he attempted to step up in class. He first qualified for the Western Golf Association’s Amateur Championship in 1908 and he qualified for it in several other years; but only one example, in 1915, of his surviving the first round of match play has been found and he was eliminated in the second round. To be fair, the Western Amateur was a tough neighborhood in those days with Chick Evans and Bob Gardner, who each won two USGA Amateur Championships (plus an Open for Evans), leading the way. In 1911, Evans was rated at scratch and Diddel, at the best number of his career, was a -3 handicap.

He attempted on multiple occasions to qualify for USGA Championships without success.

One outside-of-Indiana championship in which Diddel had some success was the Championship of the Central Golf Association, which he served as secretary. The CGA incorporated clubs from Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois except for the Chicago District.

It had 196 member clubs in early 1915. Its championship was said to be almost as strong as that of the Western Golf Association, but the Chicago exclusion left out some strong golfers. To show how much difference the Chicago players might have made, a four-man Chicago District team won the Olympic Cup at medal play in July of that year with Diddel’s team from the CGA finishing 27 strokes behind over 36 holes. Bill Diddel, who never got far in the Western Amateur, won the CGA’s first two championships (the first at Highland, Diddel’s home club) before it, presumably, was interrupted for two years by the war.

Diddel was a regular in club play around Indianapolis. It was reported that he belonged to so many golf clubs that he couldn’t keep the fixture schedules straight. He was regarded by one sports writer as the second-best amateur golfer in Indiana in 1930. Diddel became one of the first four inductees into the Indiana Golf Hall of Fame when it was founded in 1964.

While a member of the Highland Country Club, Diddel was tasked with building a course for the club that had been planned by Willie Park, by which it was meant that Park had provided a single sheet of instructions and visited a few times to inspect progress. It is difficult to tell how quickly his design business grew, but by the end of the decade he was recorded in the U.S. Census as being a golf course architect and he was regarded, at least in the region, as one of the best in the country.

His projects ranged from a reconstruction of the Coffin course in Indianapolis as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project (which, as a make-work program, employed “nearly 1,000 men”) to resort courses at Hot Springs, Ark., and at a new hotel near the entrance to the Great Smoky Mountains south of Knoxville, Tenn. He designed the original nine-hole Indianapolis Motor Speedway course in 1929, then redesigned it as an 18-hole course decades later. Both courses were used for professional tour events with the professionals having to work harder to score on the revised course. Diddel designed the Northwood course where Julius Boros broke Ben Hogan’s string of three U.S. Open wins in three attempts in 1952. He also worked as a landscape architect.

As noted earlier, Bill Diddel was a co-founder of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. He would serve twice as the president of the ASGCA (1954-55 and 1965-66).

Compact golf

Diddel watched the advancement in golf equipment with anxiety, as he had seen such advances require countermeasures in course design to keep courses from being overpowered. He believed that it would be increasingly difficult to find land for the kind of courses that would be needed to defend par. To address these concerns, Diddel responded in several ways.

In the spring of 1932, Diddel and five partners opened the Trey-Par course north of Indianapolis. This was an 18-hole short-game course that “provided plenty of practice with mashie-niblick, niblick, and putter.” There was an adjacent practice range for those wanting to hit the ball farther. This anticipated Dave Pelz’ idea for short-game courses by half-a-century.

At about this time, the USGA introduced the “balloon ball,” whose larger diameter was intended to slow the trend toward golf balls flying greater distances. It was not a popular projectile, but Bill Diddel, never one to miss pouncing on an opportunity to use less real estate for a golf course, came down solidly in favor of it, stating that the difference in playability was in the golfer’s mind.

Long before Jack Nicklaus and his Cayman short-flight golf ball, Bill Diddel had been interested in the idea of golf on smaller courses with special balls made for the purpose. Golf architect and former ASGCA president Bill Amick spoke of how Diddel proposed to Cincinnati’s municipal recreational department that it build small courses in its parks that would introduce citizens to the game of golf at an affordable price, which hints at a relevant solution in 2022. Amick told me that Diddel thought that golf should have a version of itself that would be analogous to softball for baseball or pickleball for tennis.

Diddel appealed to manufacturers for balls that would fly a shorter distance while providing a real golfing experience, but he was dissatisfied with how they flew. Amick has one of these balls that Diddel gave to him when Amick was his architectural apprentice in the 1950s.

Woodland

If there could be said to be an analog to Donald Ross’ Pinehurst No. 2 in Bill Diddel’s life, if would have been the Woodland Golf Club near Carmel, Ind. He had purchased 160 acres of farmland in Hamilton County in 1928. He said that from about 1930, when the Great Depression started, he did not have a private commission to build a golf course for about 10 years. He subsisted on golf course projects for the WPA and lost nearly everything but the property. After close to three decades of building golf courses for other people, during which he had spent about 20 years dreaming of building his own course, Diddel’s Woodland opened in April 1953.

Woodland opened as a daily fee course, but it did not stay that way for long. Hamilton County lacked a private country club and there was a movement to take Woodland private. Diddel set a deadline of January 1956 and agreed that if 300 charter members were recruited he would lease the course to the club and build a clubhouse and a swimming pool. The deadline was met and the Woodland Country Club was established. In addition to collecting the lease fees, Diddel sold building sites for homes around the course. After decades of waiting and planning, his farmland investment was paying off.

As he had intended to be the operator of the course, Diddel’s intent was to keep the cost of maintenance down. One of the ways that he did this was to design Woodland with no bunkers. He said that golfers hated bunkers and that by leaving them out he could mow everything but the greens with tractor mowers. At the start, he maintained the course with a crew of seven full-time workers, but he expected the head count on the crew to decrease as the turf matured.

As indicated by his comment about golfers hating bunkers, pleasure of play was also a part of Diddel’s philosophy. “The average club has about five golfers who want a tough course,” said Woodland’s designer. “The rest want one hard enough to gain some satisfaction from a good score, but not so full of hazards that they spend most of their time fighting out of trouble.” Diddel said that if golfers could stay out of the trees (the fairways averaged about 60 yards wide), Woodland played 20 to 30 minutes faster than most courses did.

Lest anybody think that Woodland was a pushover, the shortest tees totaled 6,410 yards and from the tips it was 6,716 yards, which, surely, was plenty long for a public course in the early 1950s. The fairways looked pretty flat, but there were subtle undulations and a few more obvious slopes. The greens varied in shape, but the general pattern was that the greens were wider than they were deep, which, in the context of his intent to make a round at Woodland enjoyable, might suggest that he thought that golfers were better at getting the right distance than they were at direction, so Woodland offered longer putts, but less chipping and pitching. After four months of play, Woodland professional Bill Heinlein’s one-over-par 73 was the course record. Diddel, then age 69, had gone around his creation in 76. “It isn’t an easy course,” he said. “You have to think on your approach shots.”

Indianapolis area golf course architect Ron Kern, who knew Bill Diddel because his father, Gary, also an architect, had been mentored by him, told me that if Diddel courses had a characteristic feature, it was that they were more difficult than they appeared to be for the better golfer while being manageable for lesser golfers. He told of what he called “Diddel bumps” that would be placed in front of greens and cited a couple of his own holes where he had employed this feature. He added that, for his own play, Diddel favored the use of less-lofted clubs rather than wedges around greens. The lack of bunkers at Woodland may have suited his style. Kern complimented Diddel’s skill at routing a course to utilize natural features.

Bill Diddel took four years to build Woodland. In addition to designing, building, and owning it, he and Helen lived in a log cabin on the property where Pete and Alice Dye visited him in search of advice when they were considering going into golf course design. Diddel warned them that it was an uncertain living. The Dyes decided to take the plunge and the rest is history.

There is a story that Ben Crenshaw’s course design firm had declined to participate in an updating of Woodland on grounds that it should be left as it was. Instead, the job of revising Woodland went to Pete Dye, whose wife, Alice, was a local native. In 2002, Woodland unveiled what I think of as the TPC-ization of Bill Diddel’s course, with what looks like 100 bunkers (and, surely, the high maintenance costs that Diddel had striven to avoid) and more places to drown a golf ball than the original designer had intended to provide. It is fair to ask whether it is Diddel’s or Dye’s vision that golf in 2022 needs more of.

The revision of Woodland illustrates a problem with Diddel courses. In 1949, an article about Diddel had the ironic title, “Bill Diddel’s work is permanent,” but while a Donald Ross course may get a loving restoration, a Bill Diddel course tends to be seen as a target for “improvement.” Prominent architect and GHS member Mike Hurdzan told me that he had played a few Diddel courses, which he described as “fundamentally sound and fun to play.”

Later golf

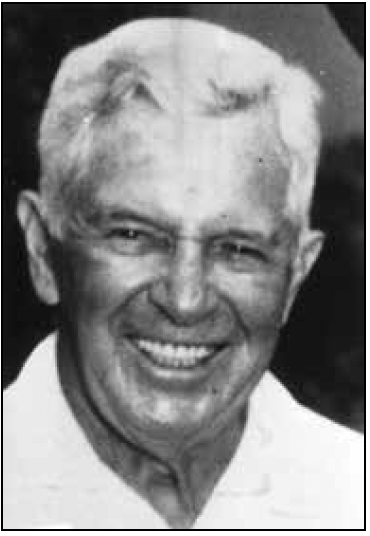

I still haven’t determined when Bill Diddel stopped playing golf. It wasn’t before age 95.

Diddel should have had a royalty contract with the Associated Press, as it seemed like a story about him doing something related to golf that was remarkable for his age was always available when there was a small space on a sports page somewhere in the United States to be filled. He was said, in Ripley’s Believe It or Not, to have scored his age or better 1,000 times; some estimates were as high as 2,000. He was reported to have beaten his age by 11 strokes at age 84.

In 1985, at age 71, Diddel qualified for a USGA Championship, its first Senior Amateur Championship (“senior” started at 55 in those days). His 80 missed the match-play by a stroke. At 73, he reached the semi-finals of the North and South Seniors Tournament at Pinehurst. In the 1961 American Seniors Golf Association tournament, Diddel, who was the oldest player in the field at 76, lost to Jack Russell, the youngest in the field at 55, when the latter holed a 45-foot wedge shot on the last hole to win by 1 up.

In 1962, the Big Cypress Golf Club of Naples, Fla., held a day to honor Diddel, who had designed its course. At age 78, his 75 tied for the low score in a field of 125 amateurs. In 1965, Diddel and fellow National Senior Champion Jim McAlvin won the over-55 Winter Season flight in a tournament at Shawnee. Despite being 82, he refused to ride in a cart during the event. On the occasion of his 90th birthday, he was quoted in an AP story as saying, “I’m just a decrepit old athlete who keeps on trying because I’m too hard-headed to quit.” At the time, rheumatism had kept him from the course for a bit, but he expected to be back at it in a couple of weeks. Before that, he had been scoring in the low 80s and he lamented that he wouldn’t be doing that for a while. “Even the high 80s,” he said, “is bad for anybody who knows as much about golf as I do.”

William Hickman Diddel died on Feb. 18, 1985, during his 101st year and was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. There was a full-circle aspect to his final resting place. From the top of Crown Hill, about 85 years earlier, young Will Diddel could see the old Indianapolis Golf Club (now the Woodstock Club), and it was from there that he first saw people playing the game that would define his life.

Acknowledgments: I appreciate the help and/or encouragement that I received from architects Bill Amick, Mike Hurdzan, and Ron Kern, and from Maggie Lagle at the USGA Golf Museum and Library, and Beth Swift at Wabash University. A listing of Diddel courses can be found variously on Wikipedia and in The Architects of Golf, (1993), by Cornish & Whitten.

Curt Fredrixon is the secretary for the GHS and a keen golf historian. His articles have appeared both in The Golf and Through the Green (British Golf Collectors Society).