Canterbury photos by Gary Kellner unless otherwise noted.

By Matthew Vazzana

The first one hundred years at Canterbury Golf Club were extraordinary. Built in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, Canterbury’s first century saw the club serve as host to many significant tournaments for both professional and amateur golfers alike, among them: two Western and U.S. Opens; two U.S. Amateurs; four Senior TPCs; three Ohio Amateurs; a PGA Championship; a Senior U.S. Open; and a Senior PGA Championship. All tallied, the club can proudly claim to have hosted 13 major golf championships, a feat only matched by its impressive list of champions who won those tournaments. Rare talents such as Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, Ralph Guldahl, Lawson Little, Walter Hagen, Bill Campbell, Mark O’Meara, Chi Chi Rodriguez, and Dave Stockton grace the club’s wall of champions in a display that makes the club equally proud as the winners themselves. Indeed, no fewer than nine of Canterbury’s tournament champions have been enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame. This remarkable run of championship golf for some of the 20th century’s best golfers laid the groundwork for Canterbury to be positioned as one of only two clubs in the country to have hosted all five of the men’s major championship events that rotate venues. And upon completion of the 2009 Senior PGA Championship, Canterbury became just that. But, as with all great golf clubs, it is not just the exciting statistics that bring meaning to the club – it is the stories behind these numbers that truly resonate and bring to life the magic of Canterbury’s tales.

The first one hundred years at Canterbury Golf Club were extraordinary. Built in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, Canterbury’s first century saw the club serve as host to many significant tournaments for both professional and amateur golfers alike, among them: two Western and U.S. Opens; two U.S. Amateurs; four Senior TPCs; three Ohio Amateurs; a PGA Championship; a Senior U.S. Open; and a Senior PGA Championship. All tallied, the club can proudly claim to have hosted 13 major golf championships, a feat only matched by its impressive list of champions who won those tournaments. Rare talents such as Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, Ralph Guldahl, Lawson Little, Walter Hagen, Bill Campbell, Mark O’Meara, Chi Chi Rodriguez, and Dave Stockton grace the club’s wall of champions in a display that makes the club equally proud as the winners themselves. Indeed, no fewer than nine of Canterbury’s tournament champions have been enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame. This remarkable run of championship golf for some of the 20th century’s best golfers laid the groundwork for Canterbury to be positioned as one of only two clubs in the country to have hosted all five of the men’s major championship events that rotate venues. And upon completion of the 2009 Senior PGA Championship, Canterbury became just that. But, as with all great golf clubs, it is not just the exciting statistics that bring meaning to the club – it is the stories behind these numbers that truly resonate and bring to life the magic of Canterbury’s tales.

Canterbury’s Founding and Early Support of Women’s Golf

Canterbury Golf Club was officially established in 1921 by John York and Lynn Ellis, two University Club members who had been bitten by the golf bug but had no such outlet to play. To scratch the itch, the two lobbied the University Club’s Board to install a putting green. Though allegedly successful in this endeavor, they soon learned that a putting green would not be sufficient to support their newfound passion. So they began hosting challenge matches at local golf courses, pitting York’s Red Team against Ellis’ Blue Team, with the losing team picking up the dinner bill for the victors. The events were popular, and it soon became clear that there was a growing interest in building a new club in Cleveland that focused largely on golf. And out of the Red vs. Blue challenge matches, the initial roster of charter members for a future golf club (made up primarily of fellow University Club members) emerged. Today, York and Ellis’ Red vs. Blue match is still played at Canterbury, now titled the Men’s Locker Room Challenge.

Canterbury’s prospectus, dated Dec. 7, 1920, held that a new golf club was to be located near Cleveland, Ohio, and it identified “the shortage of golf clubs in Cleveland and the demand for additional high-class courses” as the driving factors behind its creation. It explained that two unnamed golf course architects evaluated the potential site and opined that: “The land selected offers the possibility, at much less than the anticipated expense, of making the finest [golf] course in Cleveland and one of the best in America.” Those two golf course architects were later revealed as Herbert Strong and C.H. Allison. At the time, Strong estimated that a golf course could be built at the proposed site for $75,000. The founders, impressed with Strong’s resume of designing championship-level golf courses, selected him to design their new course. Drawings and models were completed throughout the winter of 1921 and they predicted June 1922 as the official opening.

Canterbury Golf Club was chosen as the name of the new club, not as a reference to Canterbury, England, but rather to the birthplace of Cleveland’s founder, Moses Cleaveland, who was born in Canterbury, Conn., in 1754. Canterbury Golf Club officially opened for play on July 1, 1922, with a golf tournament and inaugural dinner that recorded 176 members in attendance.

From the outset, Canterbury permitted wives, unmarried daughters, and sisters of male members to belong to the club, an uncommon practice for clubs at the time. And in an unprecedented move, before the club had even officially opened, Canterbury’s first head golf professional, Jack Way (and later, superintendent and general manager), hired Gertrude MacAdams Harrison to instruct Canterbury’s female members in the game of golf. It is widely believed that this appointment made history with MacAdams Harrison becoming the country’s first female club golf professional. But she did not stop there. While managing her duties as an assistant golf professional, MacAdams Harrison ran a golf school out of the Hanna Building in Cleveland.

While many other golden-age golf courses were left alone in their primary years, Canterbury’s founders embarked on serious, substantive changes to Strong’s design only five years after the club opened. While the front nine and the final three holes remain primarily as originally laid out by Strong, Canterbury’s back nine was significantly altered before the club even hit its 10-year anniversary. Faced with complaints concerning play backing up as groups made the turn, due in large part to hole 10 playing as a par-3 (as well as member dissatisfaction relative to hole 10’s tee box being located adjacent to a septic system), Canterbury Green Committee Chairman, Spencer Duty, and Head Professional, Jack Way, embarked on an ambitious course renovation plan that involved securing additional land for the course to permit an entire reconfiguration of the original holes 10 through 15. In making these changes, they lengthened the course and eliminated the original par-3 10th hole. At the time of the renovations, Canterbury members believed that change was needed to the course to position the club as a potential national championship venue. Looking back, it is hard to argue with their wisdom and forethought. Indeed, within five years of the completion of the rerouting of holes 10-15, Canterbury would be selected to host the 1932 Western Open and begin an enduring legacy of bringing golf’s biggest stars to the club to compete.

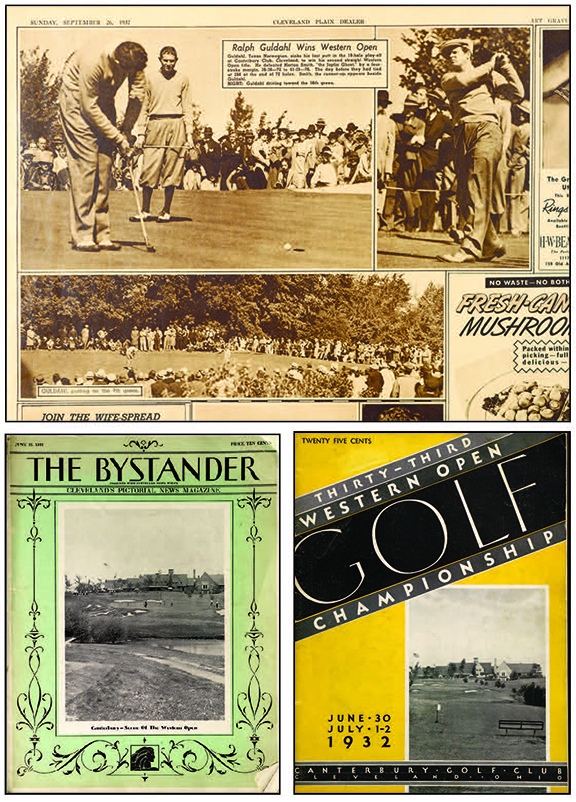

The 1932 and 1937 Western Opens

Fresh off the excitement of a newly redesigned golf course, Canterbury President E.B. Roberts announced on Jan. 23, 1932, that Canterbury would host the Western Open that year. The tournament would be played the week following the 1932 U.S. Open, where Gene Sarazen would claim a three-shot victory over Bobby Cruickshank and Philip Perkins. Notably, Sarazen subsequently withdrew from the ’32 Western citing exhaustion (a reasonable excuse given that Sarazen had just won both the U.S. Open and Open Championships in June of 1932).

Canterbury member Spencer Duty (who was instrumental in the course’s late-1920s redesign) commented on the course before the 1932 Western Open tournament, saying: “There have been no changes made because of the tournament, and if any are made, they will be slight in character. Canterbury has been developed to provide enjoyable golf to all, and it is not proposed to alter this condition.”

The pace was set on day one by Inverness Club’s Head Professional, Alfred Sargent, with a 69 for the opening round. However, it was Walter Hagen who, in classic Hagen form, arrived near his start time on day one, rolled a few practice putts, and walked straight to the first tee without playing any practice rounds, who became the eventual winner. The contest ended with a duel between Hagen and Olin Dutra. In the final round, Hagen found himself three shots down with four holes to go. Hagen fought back to one down heading into the last three holes. A par for Hagen at 16 evened the score as the players headed to the 230-yard par-3 17th hole. Hagen masterfully executed a one iron off the tee and carded a birdie, for a one-shot lead over Dutra, which he would ride to the clubhouse and claim his record fifth Western Open championship.

Four and a half years after Hagen won the 1932 Western Open, the Western Golf Association returned to Canterbury for the 1937 Western Open. Interestingly, Olympic gold medal swimmer and Hollywood’s “Tarzan,” Johnny Weissmuller, entered the field as a competitor, but he missed the cut. Other notables in the field included Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Harry Cooper, and Ralph Guldahl. Snead took the lead after day 1 and maintained a one-shot lead at the halfway point. After four rounds, Horton Smith and Guldahl tied for the lead at even par. Snead finished one shot off the lead after missing a three-foot par putt on the tournament’s 71st hole, which caused him to famously say later that he would much rather face a rattlesnake than a downhill two-footer at Canterbury. Guldahl easily won the 18-hole playoff, beating Smith by four shots, marking his second consecutive win at the Western Open championship. He won his third consecutive Western Open the following year (in 1938), along with his second U.S. Open championship at Cherry Hills, besting Snead as runner-up in the Western and Dick Metz as runner up in the U.S. Open.

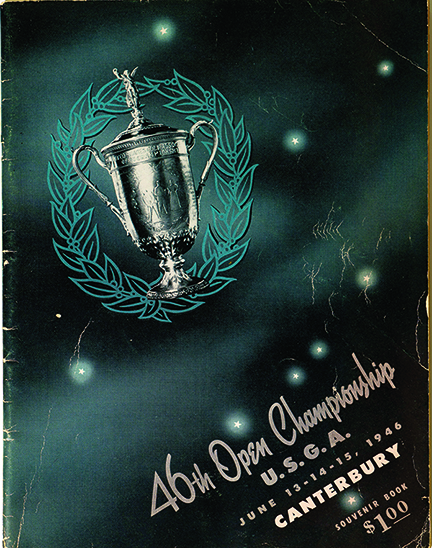

Canterbury Hosts Two U.S. Opens

Two years after the completion of the Western Open, the USGA announced that Canterbury would host the 1940 U.S. Open. The oddsmakers at the time favored such players as Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, or Jimmy Demaret to win the championship. After sitting out the ’37 Western Open and the Western prior to the 1940 U.S. Open, Gene Sarazen’s participation in the 1940 U.S. Open marked his first trip to Canterbury. Also competing was future Canterbury Head Professional Henry Picard.

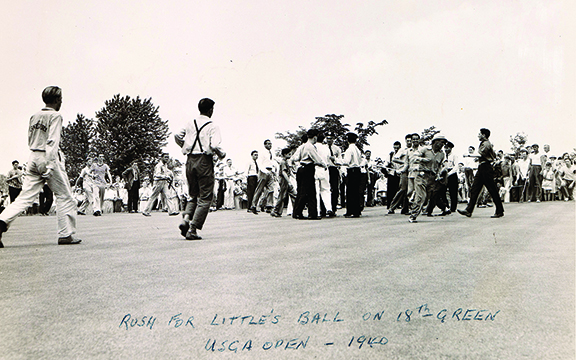

The first day saw Snead shoot a first-round low (and, at the time, course record) of 67. After day two, Jimmy Demaret’s front-round score of 41 caused him to refuse to submit his card, disqualifying him from the tournament. After his final round, Lawson Little found himself in the lead with a four-round total of 287. Snead had fallen back. Meanwhile, Sarazen positioned himself to send the championship to a playoff if he could par the last three holes.

As Sarazen approached the 18th green and 72nd hole of the competition, thousands of fans began to circle the green. Reflecting on his walk up the 18th fairway, Sarazen later recalled: “…I saw something that affected me as strongly as anything I can remember in my thirty years of golf. On the rim of the green, behind my ball, his arms extended wide on both sides to keep the crowd back, stood Walter Hagen pleading with the spectators to stand back. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, you’ve got to move back,’ I heard him say. ‘The man who is going to putt this ball is one of the great champions of all times. The least we can do is give him the room he needs’.” At Hagen’s command, the crowd moved back. Sarazen got his par and sent the championship to an 18-hole playoff where Little won by three shots.

When most people think of the 1940 U.S. Open, they think not of its champion, Lawson Little, but of the unforgettable consequence that Ed “Porky” Oliver faced for beginning his round early to avoid bad weather. And while he did successfully outrun the storm for the start of his fourth round, he could not escape disqualification for the improper start time. Other players were disqualified, but it would prove to be most detrimental for Porky, who found himself tied for the lead at the conclusion of regular play for the tournament. As a result of the infamous call by USGA officials, Porky was not permitted to play in the 18-hole playoff with Sarazen and Little. As a testament to the sportsmanship and competitive zeal that has long since distinguished golf from other sports, Sarazen and Little remarkably lobbied officials to overturn the disqualification and permit Porky to compete in the playoff. But rules are rules. Porky left Canterbury in the very regrettable position of being both technically tied for first place and disqualified.

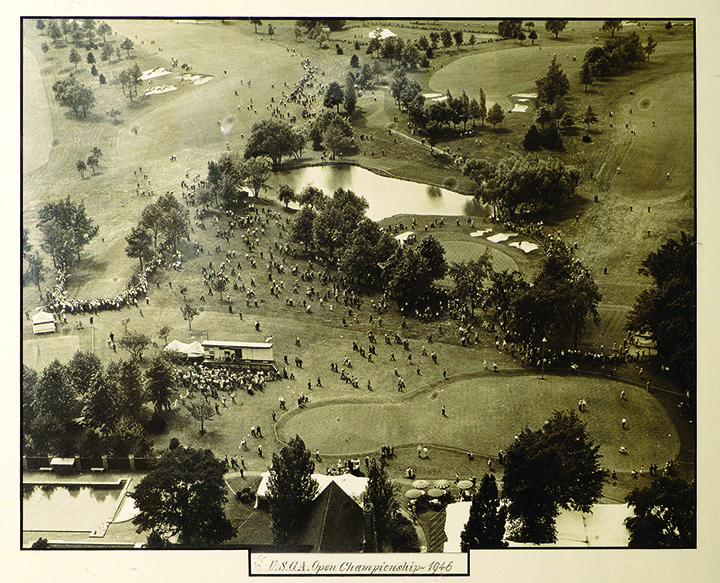

The U.S. Open returned to Canterbury in 1946. The favorites were Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, and Sam Snead. As with the 1940 U.S. Open, the championship was determined by a playoff with three players vying for the win: Lloyd Mangrum, Byron Nelson, and Vic Ghezzi. All three players tied at even-par 72 after the first 18-hole playoff, necessitating a second 18-hole playoff. Ultimately, Mangrum prevailed in a battle fought largely over Canterbury’s famed final holes. And just as in 1940 with Porky Oliver, misfortune struck one of the leaders during the tournament. Nelson, who would go on to lose in the playoff, nearly won the tournament outright, were it not for a rather uncommon one-stroke penalty he suffered during round three. After hitting his shot into the trees on hole 13, his ball bounced back into the fairway. During the crowd’s celebration and excitement relative to Lord Byron’s good luck, Nelson’s own caddie stepped on his ball and moved it. His caddie’s “misstep” cost Nelson one shot and a possible outright win of the 1940 U.S. Open in regulation play.

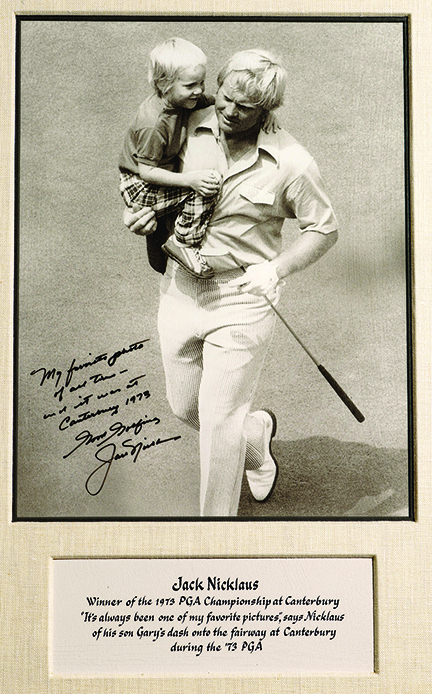

Jack Nicklaus Surpasses Bobby Jones’ Record at the 1973 PGA

In 1964, Canterbury hosted its first U.S. Amateur. It would be a memorable battle with career amateur Bill Campbell defeating his longtime rival Ed Tutwiler to finally win the U.S. Amateur, a title he had sought for many years. Canterbury again hosted the U.S. Amateur in 1979, where Mark O’Meara would begin a storied golf career with his win over defending champion John Cook. Between these two U.S. Amateurs, Canterbury hosted the 1973 PGA Championship – a tournament that would forever cement Canterbury’s place in golf history.

The 1973 PGA Championship was the 55th playing of the annual major tournament hosted by the PGA of America. Jack Nicklaus had been searching for a major championship victory throughout the 1973 season. He had come up short at Augusta, Oakmont (U.S. Open), and Troon (Open Championship), and the PGA Championship at Canterbury would be Nicklaus’ last shot in 1973 to clinch his 14th major. Ultimately, Nicklaus won by four shots over runner-up Bruce Crampton. It would become his third of five PGA Championship titles that he would earn throughout his professional career. The 1973 PGA is undoubtedly most famous for being Nicklaus’ 12th professional major championship win. However, coupled with his two previous U.S. Amateur titles, Nicklaus now had 14 major championship titles to his name. With his 1973 PGA Championship win at Canterbury, Nicklaus surpassed Bobby Jones’ record of 13 major championships (which included five USGA Amateur titles and one British Amateur title), becoming the record holder for the most major golf championship victories in history. (“Majors” in Jones’ day included national amateur victories. Jones never played in a PGA championship.) Nicklaus would win four more professional majors, for a total of 18 professional major championships. To this day, Nicklaus’ record for the most major golf titles (including Amateur victories) still stands – a record initially set at Canterbury with his win at the 1973 PGA Championship.

Canterbury’s Future

After closing out its first century by hosting two more majors, the 1996 U.S. Senior Open and the 2009 Senior PGA Championship, Canterbury’s second century is poised to be just as exciting as its first. In October 2022, the USGA announced that it had chosen Canterbury to host the 2027 U.S. Girls’ Junior, the 2033 U.S. Senior Amateur, and the 2039 U.S. Women’s Amateur. These three championships will mark Canterbury’s sixth, seventh, and eighth USGA championships.

The members of Canterbury Golf Club are exceptionally proud of the golf course and the club’s rich history. As stewards of the game, we have an important responsibility to recognize, preserve, and share golf’s rich history with current and future players and fans alike.

GHS member Matt Vazzana is the Club Historian at the Canterbury Golf Club in Cleveland, Ohio. Matt is also a director of The Canterbury Heritage Foundation which works to preserve and share Canterbury’s rich tournament golf history, partly through an annual invitational tournament showcasing the best boys and girls high school golf teams in Ohio. He is managing the publication of a forthcoming book that recounts the first one hundred years of championship golf at Canterbury.

GHS member Matt Vazzana is the Club Historian at the Canterbury Golf Club in Cleveland, Ohio. Matt is also a director of The Canterbury Heritage Foundation which works to preserve and share Canterbury’s rich tournament golf history, partly through an annual invitational tournament showcasing the best boys and girls high school golf teams in Ohio. He is managing the publication of a forthcoming book that recounts the first one hundred years of championship golf at Canterbury.