Through the years creative clubmakers have sought to add a little “oomph” to impact.

By Dennis Hucul

For decades adding extra distance to your shots has been a highly sought-after goal. Most modern drivers have relatively thin faces that flex to help add extra distance to tee shots. More recently people have referred to this as the “trampoline effect.” This article describes some of the early attempts to add extra distance to shots.

Some of the clubs mentioned in this article were manufactured in very limited quantities, but descriptions are included to help understand some of the ideas that were considered. Although no actual photos of these clubs are available, they are reviewed to give the reader a better feel for the thinking at the time.

As you will see, the idea to help add extra yards to shots is far from new. As early as 1893 people have developed methods to produce a spring-like effect and work on improving this effect continues even today.

The earliest spring-faced club that can be documented was detailed in Patent 3822 in 1893 by William Ross from Nottingham, England. He designed a cavity in the face of a wood or iron that would be covered by a thin steel plate. According to the patent, the thin metal plate may be flat, convex or concave depending on the purpose of the club. Although the patent describes spring-faced drivers and spoons it appears that not many survived. Even the irons are extremely rare. Pictured at the top of this article is a Ross cleek showing the thin metal plate attached to the face by three brass rivets (see The Clubmaker’s Art by Jeff Ellis).

Jennings Patent

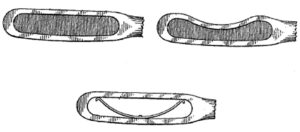

In 1894 William Jennings from Toronto, Can. applied for a U.S. patent for a golf club head made of spring steel with the metal shaped “so as to leave resilient steel walls surrounding a central space, which preferably has a metal spring or a filling of elastic material.” Jennings was granted U.S. patent 550,976 on Dec. 10, 1895. The drawings below are from the Jennings patent and are seen from the perspective of looking up at the bottom edge of the iron.

The top two show the gutta percha-filled iron heads before and after impact. The bottom drawing shows a bent metal spring in the empty cavity instead of gutta percha. (Also equivalent to patent No. 19361 from Great Britain in 1894).

Walker Patent

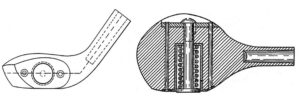

In 1895 George Walker, a clockmaker, received Patent GB 1554 for a different style spring-faced club. To add elasticity Walker added a metallic spring to the head of a wood or iron. This spring covered almost the entire face except where it was attached to the body of the club. This convex section of spring steel was designed to flex during impact of the ball giving it added forward thrust during the rebound of the face.

The diagram above illustrates an iron design using this concept along with a cross sectional view of two different style springs. A putter with this style face can be found in The Clubmaker’s Art. I have seen only one example of an iron with this type of face. It appeared to be a mashie. Undoubtably at least some others were manufactured.

Mules Patent, Great Britain

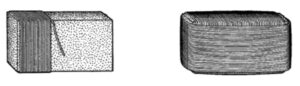

In 1900 William Mules received a British patent, No. 20069, for his concept of a wooden club head with a flex- ible face. According to his invention a recess is cut into the face of a driver and filled with gutta percha. The face is then covered with a roughened sheet of spring steel fastened with screws, the plate having direct contact with the resilient gutta percha. This design increased the “driving power” of the club. An example of this club is shown above.

Mules Patent, U.S.

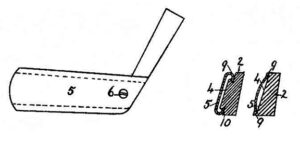

In addition to his British patent Mules also received a U.S. patent, No. 708575 from 1902, for a resilient faced club with a slightly different design (drawings shown above). In this case a rigid face plate of wood is backed by a piece of resilient material that has a different thickness across either the top or the bottom of the entire face. This variable thickness was designed to produce a more lofted shot if the resilient pad is thicker at the top (drawing at left) or if the thicker portion is close to the sole plate a less lofted shot will result (drawing at right). According to Mules, a person possessing one club of each design would be able to execute the “whished-for” (sic) stroke.

Cran Patent

James Cran, an employee at Spalding, was the inventor of a cleek that was named after him in the late 1890s. By 1902 a new version of the club, advertised as “Steel Spring Faced Golf Clubs,” were featured in Spalding’s fall catalog. Claims were made about incredible new distance on shots. The clubs featured a very thin steel face riveted to an iron club head. Many of these club heads are hollow, but some were manufactured with a gutta percha filling. These spring-faced clubs were available as cleeks, lofting mashies, and mid irons. Even a few putters were made. Many examples are known and the clubs were sold by Spalding for more than a decade. Although the clubs were stamped with a patent date identical to those that feature a wooden face insert, the steel spring-faced clubs were clearly different. The photo above shows a typical Cran spring club face – in this case manufactured by the Wright & Ditson company.

Dunn Patent

John Dunn, a well known clubmaker, describes a different idea in an article he wrote for the Aug. 15, 1902 issue of Golf Illustrated (England). In the article, titled “Compressed air face club,” Dunn writes:

“The resiliency comes from air under pressure; it will be known as the compressed air face. It is simply a cel- luloid chamber behind a face of hard gutta-percha, the whole being squeezed up tight between a flange on the face and a wooden block. The head will be of aluminium. The device is intended for gutta balls and should gladden the hearts of the gutta ball makers.”

Dunn’s article clearly states that a (British) patent application had been filed for the club, but a careful search of patents from the early 1900s reveals comes up empty. Only a very few of these clubs appear to have been made and it is doubtful if any survive.

On May 8, 1903, Dunn did receive a U.S. patent, No. 726885, for a different idea, his rubber core driver. According to this patent, a rubber core wrapped with rubber strands in either one dire tion or two was inserted into the cavity of a driver and molded in place with gutta percha. Spalding obtained the rights to this patent and sold these clubs under the heading “rubber core clubs.”

Unlike Dunn’s compressed air face club, this club, shown above, was manufactured by Spalding for more than a decade.

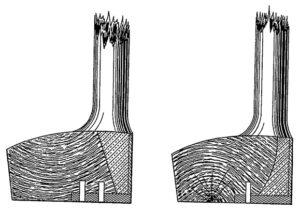

The drawings above are from Dunn’s patent and depict a rubber core covered by vertical elastic windings on the left. On the right the drawing shows a rubber core coved by both vertical and horizontal elastic windings.

Clark Patents

In 1904, Charles Clark, of Massachusetts, received two relatively obscure patents for enhanced driving distance clubs. The first, U.S. 769939 was for a club with a cylindrical plunger backed by a strong spring. Upon impact with the ball, the plunger is compressed against the spring which then provides a “sudden and severe thrust to the ball to increase the drive by accelerating its speed.” The drawings above show one version of this club. It does not appear that this club was successful and no manufactured versions are known.

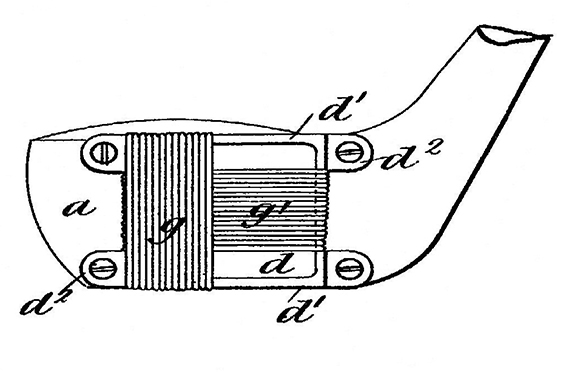

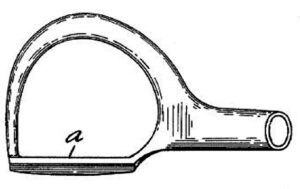

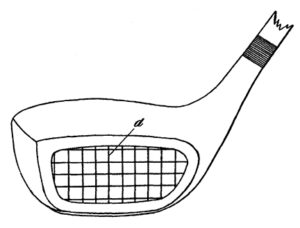

Clark’s second patent, U.S. 777400 issued on Dec. 13 1904, was for a driver that looked like a sideways “U” when viewed from above. It featured a large open central cavity with a “spring acting cord-like member” attached to each end of the U. In the drawing above, one can see the large empty central core and the spring like face labeled “a”. This club apparently fared no better than the Clark’s first patent and was never successfully manufactured.

Wilford Patent

Charles Clark wasn’t the only inventor to design a club with a relatively heavy movable face backed by a coiled spring. In 1912 George Wilford was issued British patent 17790 for a driver with a large faceplate that protruded from the front of the club. Upon striking the ball the faceplate would compress a coiled steel spring and then rebound adding distance to the tee shot. Unfortunately, as it turned out, by the time the faceplate could spring back the ball was already launched. The only thing this club accomplished was decreased driving distance due to the energy lost during compression of the faceplate. The picture above shows this very rare club.

Beale Patent

On May 4, 1906, Harold Beale applied for a British patent (No. 10441) on a method to “greatly increase the driving power” of a club. This was to be accomplished by making the portion of the face which contacts the ball a highly resilient surface formed by wire or wires under high tension (drawing above). The U.S. equivalent of this patent is No. 890836. I have never seen any examples of this wire-faced club.

Grant Patent

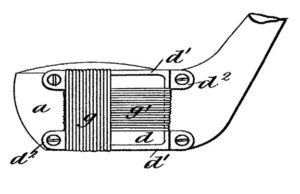

In 1909 John Grant, from London, was granted a patent (GB 2717) that focused on using “intertwined gut” as a resilient material in wood faces. The patent focused on tennis racquets or bats but did extend to golf clubs. According to Grant the face not only enhanced hitting power but reduced the jarring impact to the player. The diagram above is from his patent. Section “d” shows the intertwined gut. If this reminds you of a tennis racquet you understand his concept. It is doubtful if any such golf clubs were commercially produced.

Wilson Patent

Robert Black Wilson, a clubmaker who early in his career apprenticed for Old Tom Morris, developed a spring-faced iron club in the late 1890s. This club, shown above, had a rectangular cavity behind the face and that was filled with leather compressed between the thin face and the body of the club. It was said to have produced great elasticity that worked well with the new rubber cored golf balls. More information on this club can be found in The Clubmakers Art.

Percival Patent

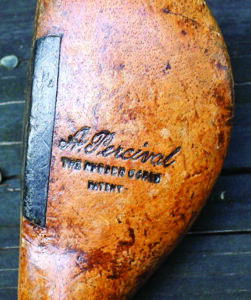

In September 1919 Albert Percival applied for a British patent titled “Improvements in or relating to Golf Clubs and the like.” Known as “Percy” to his friends, Percival was the head professional at Highcliffe Castle Golf Club in southern England from 1917 until 1940. (His great grandchildren are still members.)

Percival described his invention as a sheet of rubber sandwiched between two pieces of vulcanized fiber. A composite face plate formed by these materials was attached to a wooden head into a dovetailed vertical slot. The face is fastened to the club with glue and secured by the addition of hickory pegs (covered with vulcanized fiber). A conventional fiber sole plate was also attached to the club to slow wear of the club when striking hard ground or other materials.

Percival claimed that this new club, shown above, provided not only increased driving distances but also a long-wearing face. He received another patent in 1926 in conjunction with Ernest Whitcombe for their PerWhit putter.

Royce Patent

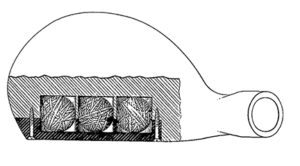

Charles W. Royce, a New Jersey resident, patented the idea of using rubber balls behind the face to increase resiliency. This patent, U.S. 925389, from 1909, was assigned to Kempshall Manufacturing Company of New Jersey. The patent describes the use of rubber balls made by winding rubber bands under tension and placed behind a recessed face plate under slight compression, (drawing below). The resiliency of the new face, it was asserted, “will considerably increase the sending power of the club.” The photo above shows an example of this club. The author had the opportunity to briefly examine a Kempshall rubber cored club with the face plate removed and in commercial production two wound rubber balls were used instead of the three shown in the patent image.

Additional developments continued throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s. For today’s clubs one technology dominates – almost all current drivers are manufactured with a thin face that flexes during impact. Spring-faced clubs would make an excellent specialist collection category that can continue with modern clubs.